From Japan / RULES FOR DRAWING

6pm Thursday 1 February to 5pm Sunday 25 February 2024

DRAW Space is delighted to present the works of 5 Japanese artists:

Tetsuya Chiba 千葉鉄也 | Rin Fukumoto 福本倫 | Kai Koyama 戸山恢 | Susumu Takashima 高島 進 | Kanae Toyama 遠山 香苗

Susumu Takashima is represented by Gallery Kazuki and Gallery Moryta

We know that really, there are no rules for drawing. To draw is a bodily action, engaging with tools and materials to various degrees, but primarily drawing is about exploration.

Contemporary drawing is often described as a journey without a destination, an open-ended process, an awaited discovery. As such, there are no rules with which to define it. The idea behind this exhibition, of rules for drawing is to present a group of artists who work methodically, systematically, and serially within a narrow set of refined and self-selected parameters. Paradoxically, this rigour opens vast tracts of drawing space for discovery. In effect, their reduced and restrictive rules create a space where the process of drawing becomes one with the results.

Drawing is such a simple, humble, and visually direct means of expression. Drawing – the making of marks on a surface - can used as a mode for exploring a visual motif, a particular materiality, the limitations of a tool, as preparation for another practice, or just because it is. A rule can be as simple as drawing only circles, making marks in single colour layers, drawing with a digital device, or devising ways to randomise compositional choices. Drawing can also be a record of unseen actions and ideas. Essentially, drawing is an action but also a journey somewhere. While there are no rules for drawing, artists are free to set rules to draw by.

The exhibition will open on Thursday 1 February and run until Sunday 25 February.

Curated by Lisa Pang.

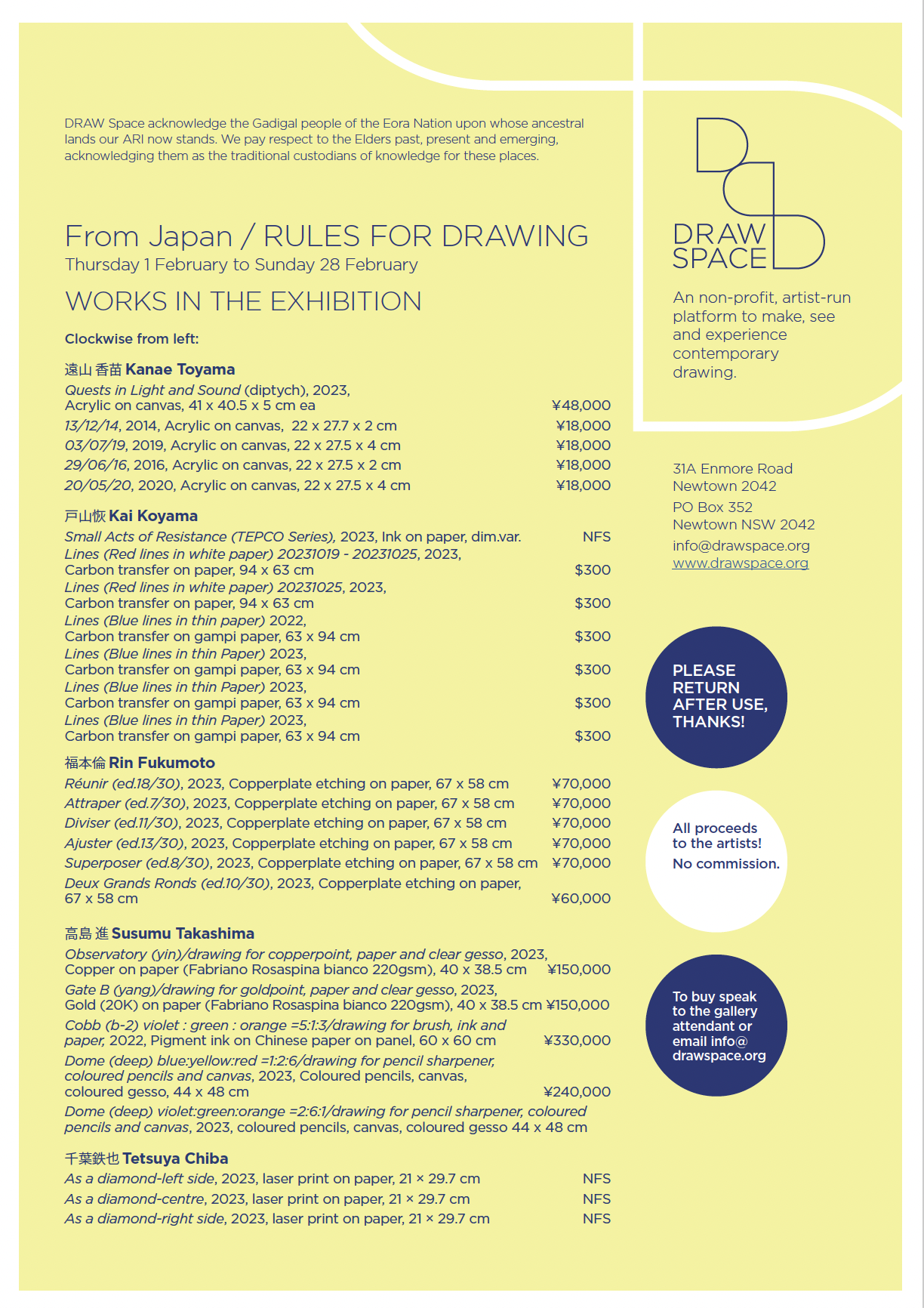

Room Sheet

Click on the image on the left to download the exhibition roomsheet.

Contact DRAW Space for purchases - email info@drawspace.org.

Review

Read Joe Frost’s exhibition review on Artist Profile Weekend Review online now.

Five journeys / Loss in translation

Exhibition essay by Curator, Lisa Pang

It was a tadaima[1], a call out. Sliding the screen door, stepping in, shuffling out of shoes.

In September 2023 I was back in Japan, a country and culture I had lived in and out of for 4 years. I had left, a little saddened, only months before, not expecting to return so soon. My e-transport pass still worked, and it didn’t take long to feel the familiar ease and multiplicity of choices when travelling the immense and convoluted ramen bowl of lines that is Tokyo public transportation. While intimidating initially, I had learnt that there are many ways to get to a destination.

One trip planner might send you intersecting across several curling and differently coloured noodle-like lines. Another app might offer an alternative way; even more colourful changes, but with less walking in between. On the platforms, columns are jammed with hieroglyphed explanations, diagramatic explainations for which carriage to ensure the swiftest transfer. Yet another way might preference a private railway, or bus. Distractions abound; consider platform melodies, a favoured food or convenience stop on an underground connection, lines haunted by odd smells, women-only carriages offering pink safe zones at peak travel times. Personally, I have a weakness for the Tokyo Metro Ginza line and often choose its cheerful yellow promise over a more direct way. As one of Tokyo’s earliest lines it runs shallower below ground, and there is also hope – a chance of a ride in a green velvet, wood panelled, lamplit retro-themed carriage.

This traveller’s internal monologue, of a series of idiosyncratic choices made while tripping, even choosing to become a little lost, is much like the role of process in drawing. It is what happens when we prioritise journeying over destination. Way over result. Means over ends. Chance over Certainty. Quirk over plans. I was in Tokyo to make 5 journeys. 5 artists who through an intense focus on their processes, have come to a set of self-imposed rules in their drawings. As drawers they are mark makers led by the marks, guided by motifs, actions, even philosophies. Like any curious traveller, they place precedence over the ways they draw, rather than seeking out a predetermined result or image. The drawings they make are distinctly non-objective. Abstracted marks, free of any desire to represent the world, and characteristically serial, these 5 journeys arrive as fragments of a larger, inward-looking exploration of process. In drawing-as-journey, the artist’s rules are really a way of achieving wonder; a mental state of acute observation, while wandering; the physical process of applying marks to blankness.

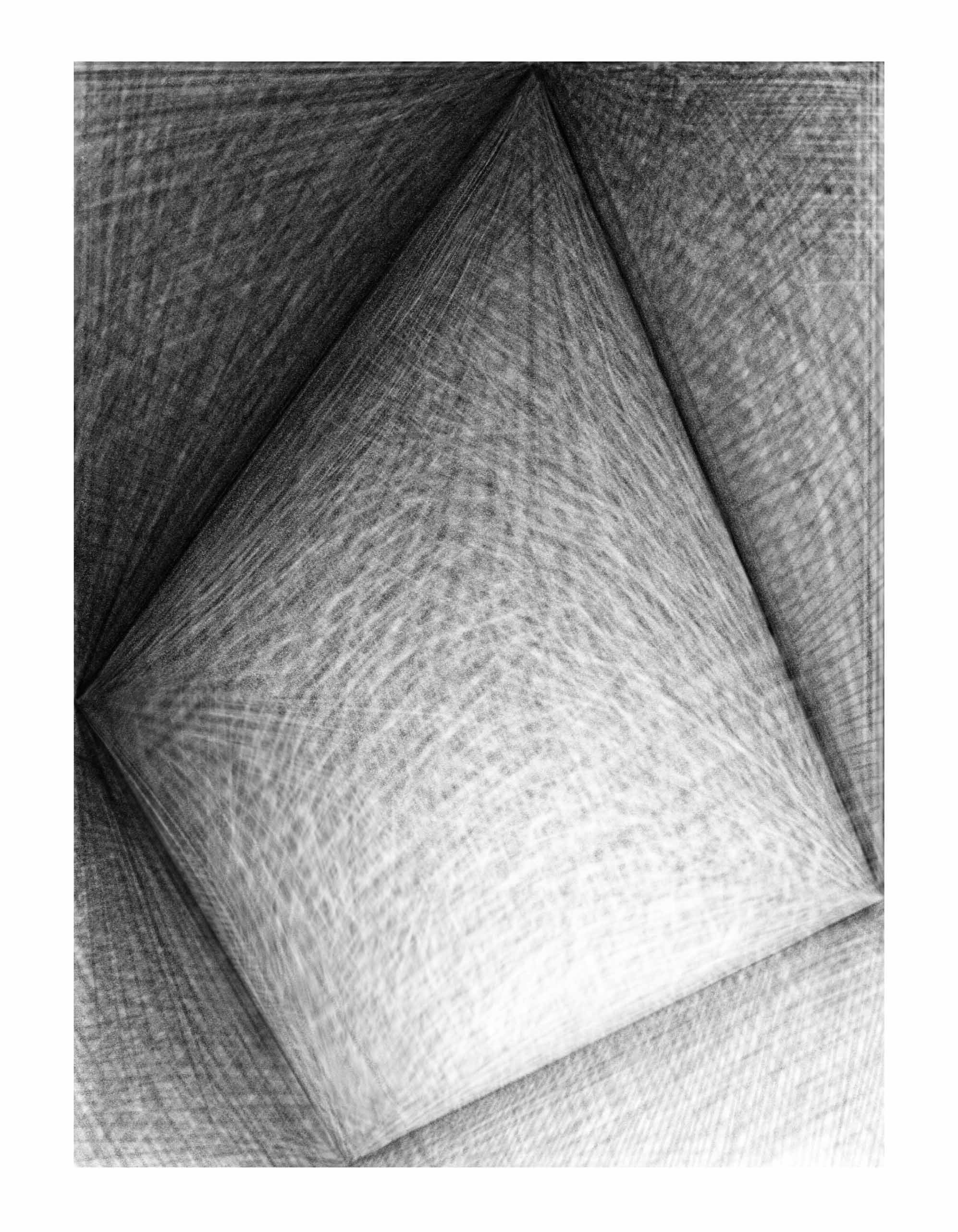

一 Journey 1 千葉鉄也 Tetsuya Chiba Oshiage – Shinjuku

Tetsuya Chiba was the last artist I was to meet and I was late. The map reference on my phone was giving me directions in Japanese and overconfident and relaxed, I was on my way to the wrong part of Shinjuku, blissfully unaware I was setting myself up for a long, fast walk to our planned meeting. When we finally met, with our partners, we sat together in a tiny booth of a game restaurant, drinking beer and sharing small, delicious plates. We generally spoke of things other than this show. In the corner, nondescript but carefully wrapped, sat a carry-bag containing the works for this show.

In a traditional and academic sense, Chiba describes his drawings as preparatory for his paintings. These fracture pictorial space into sharpened angles and planes; triangulations of thickly textured oil paint resemble facets of a jewel, after which they are often named. And yet, these drawings have another quality. Stripped of the physical tactility of paint, absent the bodily presence of the artist’s hand they present as ephemeral distillations of intention. Stripped back to compositions wrought from line alone, and drawn digitally, their grey scale and restraint are eloquent. These lines, thickened darkly here, faintly scratched there, suggest a uniformity and relentlessness of intent that underscore the richly coloured jewel-like paintings to come. ‘There are always strict rules. However, rules break down when creating a work. That will lead to progress’.[2] Drawing as preparation for painting is a rule for drawing, for the reliance on mark, visual vocabulary, and the exploration now for something to come, later.

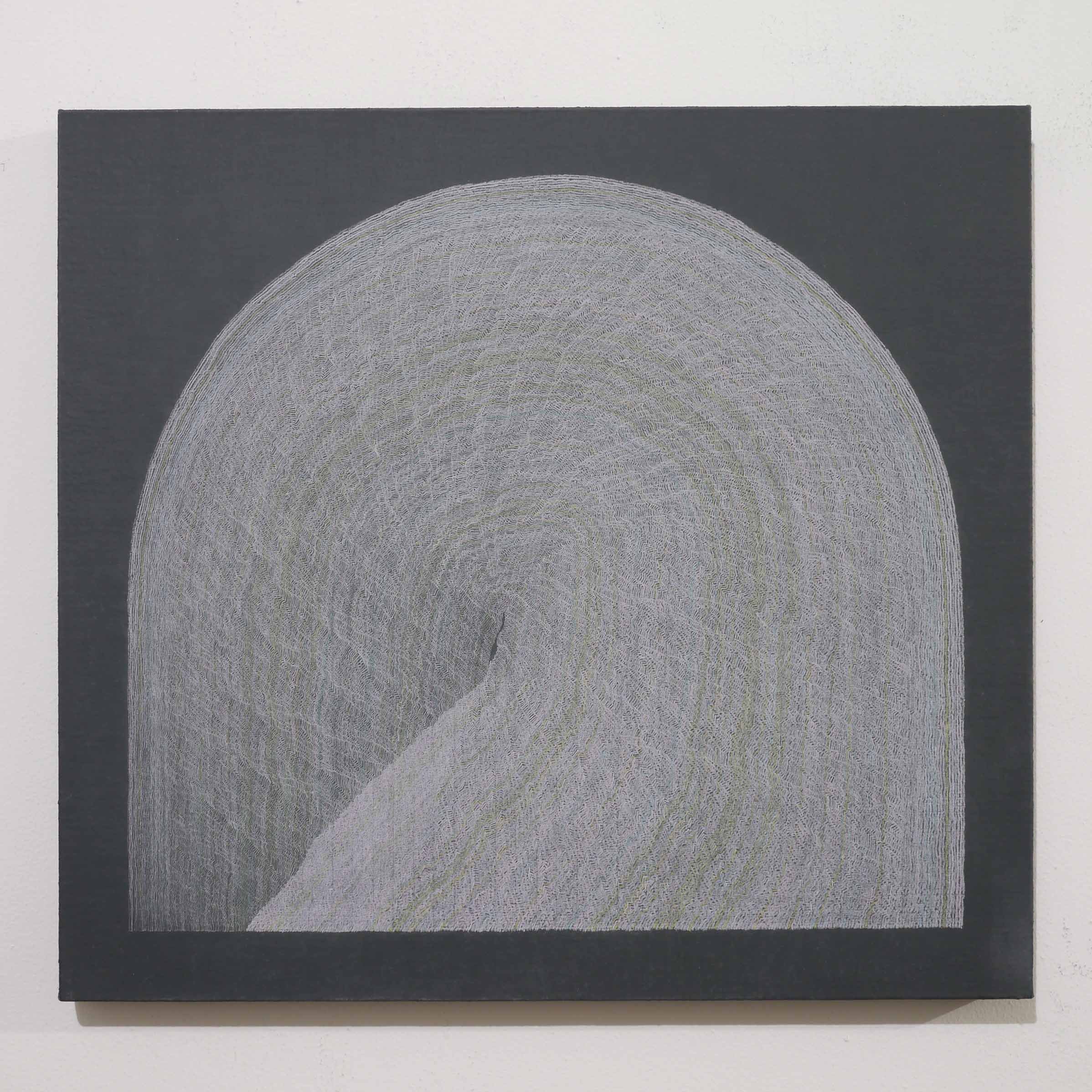

二 Journey 2 福本倫 Rin Fukumoto Shirokane Takanawa – Hibiya

A memory of a journey. It was raining outside when I walked into a solo exhibition of Rin Fukumoto’s work in Ginza. When it rains in Tokyo, people tend to be prepared, with ubiquitous translucent umbrellas sprinkling the streets. Inside, as ever widening droplets in a puddle, her works repeated the circle, deploying scale, section, texture, layer, in a sinuous repetition of the orb in a seemingly endless visual variety. The repetition of the shape in the works somehow renders the familiar mark unfamiliar. A circle is a universal motif, perhaps the first thing we learn to draw, imperfectly. In this ongoing investigation it resembles many things, a sun in the sky, a stain on a table, a well in the ground, the impression of fingertips in soft clay. Always a circle, and always, not quite perfect.

On that day, when I first met Fukumoto, unexpectedly, we could best communicate in stumbling (on my part) French. She describes a personal philosophy that informs her ongoing visual quest. As she says, ‘life begins in a circle’. The fecundity of these forms, ‘les rondes’, she observes, is common to organic forms; cells, eggs, and celestial bodies. Fukumoto draws the circle over and over to express the way life cycles of life recur ‘in a beautiful equilibrium’.[3] The mark conveys harmony as well as providing an endless source of imagery. Fittingly, when Fukumoto’s works arrive in Sydney from Japan they are rolled. Uncurled and laid out, faraway from where they were made, printed circles spill over in a tumble of warmth and vibrancy. This is drawing by rules, for the primacy of the mark, resonance of the motif and the endlessness of the question.

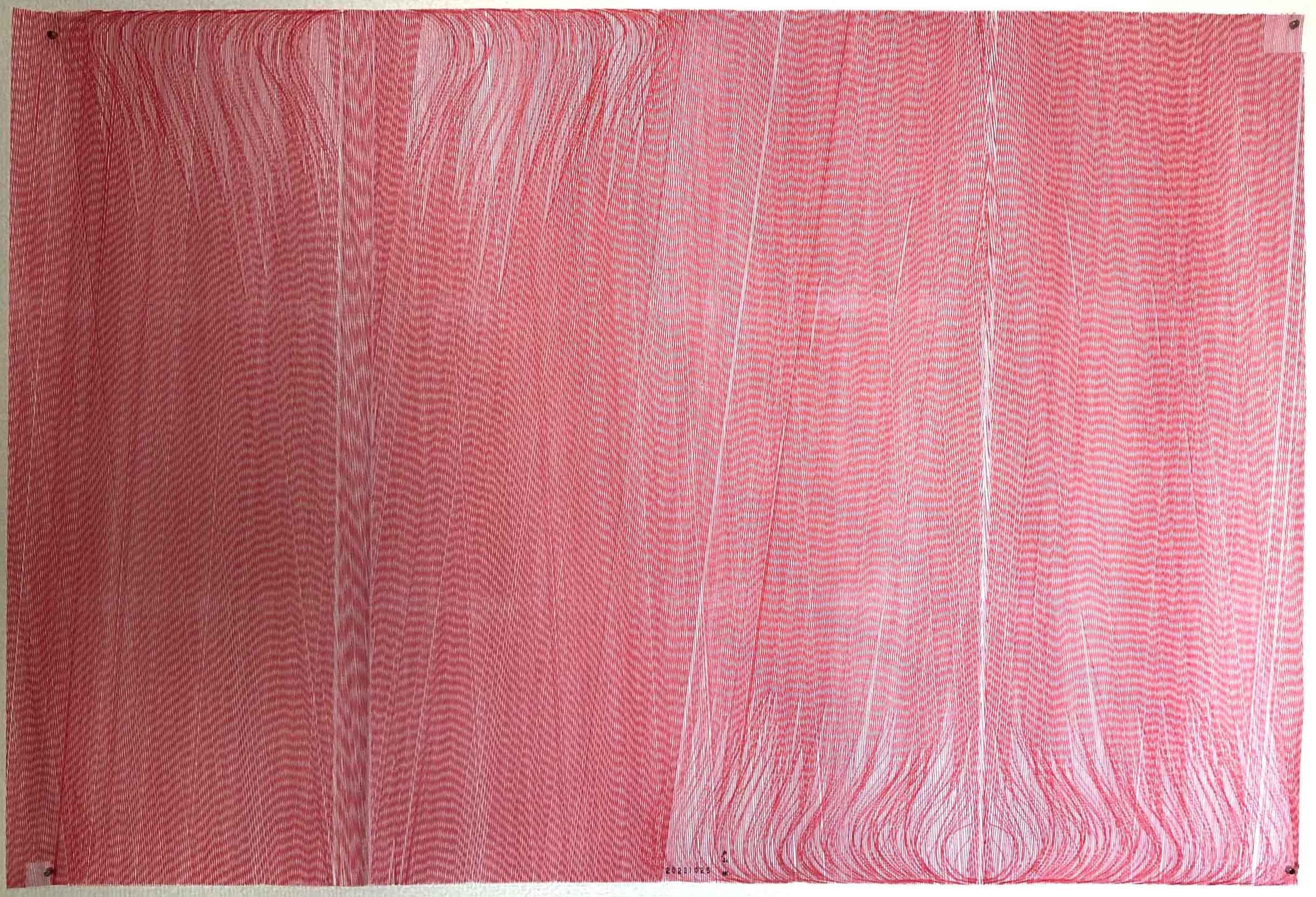

三 Journey 3 戸山恢 Kai Koyama Shibuya – Omote-sando

It was raining torrentially the September evening we met. Coming up from the subway, rainwater was gushing down the stairs in a series of small waterfalls and by the time I navigated to the calm and dry foyer of the community centre, my shoes and socks were sodden. Each step let out a soft squelch. As the rain continued to pour down outside Kai Koyama, raincoat aside, carefully unwrapped a recent series of drawings on paper (not the works in this show.) He describes his process for drawing parallel lines using a ruler as very boring work. Most recently Koyama had found an antique curved dressmakers’ ruler and, by chance, the curved line drawings made with it resembled threads woven into textiles. I remarked on their beauty, and by way of response, he spoke into an electronic translator, holding up the screen for me to read: Interesting patterns are created there. But that is not my purpose. It is a by-product. People are interested in the patterns, and I am happy about that, but my purpose is a little different.[4]

Koyama draws to record an action. This may be the simple action of attempting to draw a series of parallel lines. Using a point on carbon paper, the drawn line cannot be seen by the artists and inevitably, small jumps or deviations appear. Unseen, these movements accumulate as the drawing is continued. In another work, the action is a social protest. A methodical collection of paper receipts narrates an ongoing citizen vs. corporation action; a ¥1 underpayment of every bill. This is a rule for drawing, where multiple small actions are marked, marking its maker, time, and place in an ongoing matrix that is a drawing.

四 Journey 4 高島 進 Susumu Takashima Fujino – Nihonbashi

I had left early from the mountains outside Tokyo, where I was staying with a busily working group of textile artists. It was hot and humid, an unseasonal Autumn, and I had spent the day crossing Tokyo on multiple errands. Late afternoon, within the darkened cool interior of the Musée Hamaguchi Yozo, time slowed down as I met Susumu Takashima at his exhibition, together with a small and enthusiastic group of people he knew. A friend of the artist spoke British-accented English and was an eloquent go-between. Around us, Takashima’s highly intricate works were displayed; sensitively accompanied by torches and magnifying glasses for close looking as well as informative wall labels detailing the process. Also a drawer of parallel lines this is drawing, as is emphasised in the titling, for materials. Takashima draws, as he says not to create an image, but to discover the infinite possibilities inherent in the very materials that make up a (draw)ing.[5]

While it seems predictable to state that a continuous line drawn by a pencil thickens over time, or that a brush dipped in ink dries and fades, these are drawn marks that have effectively become their own subject. What is not predictable is the roll of a dice, a device Takashima has introduced to reduce his subjective input (choosing colour) while drawing. Time, also unpredictable, is embodied in Takashima’s work but especially in the metalpoint drawings. Slowly drawn with sharpened soft metals; copper, silver or gold lines lie within the paper and oxidise slowly, darkening inexorably over time. A sustained focus on materiality and temporality, enlivened by the role of chance, are rules to draw by.

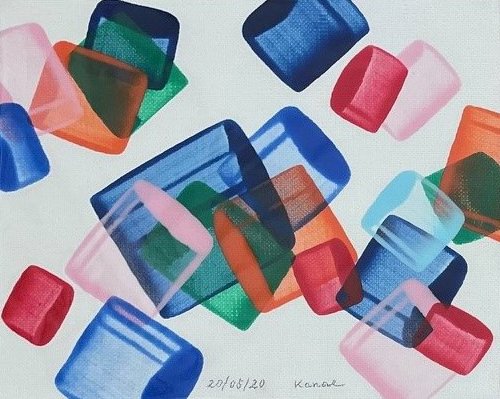

五 Journey 5 遠山 香苗 Kanae Toyama Fujino – Kichijoji

Once again I travel from the mountains to meet Kanae Toyama at an about half-way point. She had sent me a picture of a specific exit gate at Kichijoji station. On a whim I spend some time beforehand unsuccessfully searching foodshops for yuzu koshō[6]. When we meet, Toyama suggests we walk to a coffee shop where we sit in a dark timbered booth and talk about art and architecture, painting, and her chance meeting with a musician. I discover there is much more to her work than the alluring, floating clarity of translucent paint strokes. The musical quality of her paintings was already apparent; the layers of clear colour and the cube-like forms of a paint-loaded brush touching the white canvas and interacting as a crisp melody on a page. Toyama tells me of her current project in which she is developing a collaboration with the wind musician Hiroshi Suzuki, an extended back and forth dialogue in painting and music. She says, ‘I see my work as giving form to rhythms and melodies’.[7]

Much later I watch a video of Suzuki performing, and the quality of the saxophone, warm and breathy, echoes the liquid paint marks of Toyama’s painting. There is touch too – fingers on keys, brush to canvas. There is space – as pauses between notes. Colour too – in sound quality, length and in vibration. As her coloured marks do, sounds float out in a suspended space. This is a rule for drawing, in the restraint of layering one colour-mark per day, and only as a response. While the paint application on surface is slow, deliberate and controlled, there is delight in the drips and pours that happen on the edges of the canvas, breaking the reverie with whimsy. After we go our separate ways, I do find yuzu koshō and am delighted.

What’s essential is invisible to the eye. [8]

The 5 journeys I have related took place within a larger moment than my trip to Japan in September last year. There was my time seeing exhibitions in Tokyo and there was a travelling postcard project. I may not have mentioned that I do not speak Japanese apart from very superficially. The artists spoke some English, one didn’t but did speak French. So, our conversations were often halting, punctuated by assistance from others or paused as we resorted to translators. Often it was an email exchange where an explanation, phrase, or meaning broke through. While much can be said about meaning and nuance being lost in translation, occasionally it is while we are lost; stumbling and uncertain, that we look more closely at what is in front of us. Even so, often what is essential is not merely seen but is what is felt, shared, and admired. Friendships and respect grew among the drawings. There is perhaps more to be said about communicating outside spoken language alone.

Rules for Drawing is a group exhibition exploring the imposition of rules as a generator of drawing. As artists we know that really, there are no rules for drawing. There are materials, there are subjects, and there is always process. Drawing is a direct, immediate language. But when artists self-impose rules they turn away from a frontal approach and instead come upon the drawing process sideways, open to unpredictability over design in their outcomes. Essentially, drawing is an action but also a journey somewhere. While there are no rules for drawing, artists are free to set rules to draw by. Paradoxically, the rigour established by rules instead open up vast tracts of drawing space for discovery.

Lisa Pang

© January 2024

[1] Translated from Japanese, tadaima: ‘I’m home’.

[2] Extract from email correspondence between the artist and the writer.

[3] Extract from translated email correspondence between the artist and the writer.

[4] Extract from an electronically translated conversation between the artist and the writer.

[5] Extract from artist statement in catalogue to exhibition.

[6] Yuzu koshō is a paste made from fresh green chilli peppers, yuzu juice, peel and salt, which is left to ferment.

[7] Extract from email correspondence between the artist and the writer.

[8] Translated from French: ‘L’essentiel est invisible pour les yeux’: Antoine de Saint Expeury, The Little Prince.

Artist Kai Koyama held a concurrent solo exhibition, Small Resistance in Tokyo in February 2024. Below is a review written by art critic Hiroyuki Arai. (English translation and original Japanese)

The politics of minimalism: Discussion about Kai Koyama

Arai Hiroyuki Art/Culture and Social Criticism

21 February 2024

Koyama's latest solo exhibition is “Small Resistance” held at Toki Art Space from January 23rd to February 4th, 2024. This is a solo exhibition that has been held under the same title since 2021, and this year will be the third time. There is also continuity in the content of the exhibition, with the work entitled “Line” forming the main composition.

The support for this “line” is gampi paper. Lines drawn at equal intervals densely fill the screen. The lines are not drawn mechanically but are drawn using a ruler, and as a result, there are slight fluctuations or misalignments. This gives the viewer a pleasant physical sensation that goes beyond visual pleasure. This is the same principle that allows electronic music to have subtle fluctuations in rhythm rather than pure regular patterns, giving the listener a sense of familiarity and comfort.

Koyama creates works called “lines” by sandwiching carbon paper between Ganpi paper, folding it in quarters, and writing on top of it with a pen to transfer the lines. There are only three types of lines: blue, black, and red. It is said that this method was born from his daily life, where it is difficult to find the time and space for a complete production. The works are imprinted with Koyama's daily life.

Looking at the exhibition composition of his past three solo exhibitions, there are some changes. The first time, the small two-dimensional works that he had been working on were also interwoven, but from the second time onwards, “lines” were the main focus. The exception is the “Electricity Bill Non-Payment Project” that Koyama has been working on for some time, specifically, switching TEPCO's electricity bill to monthly payment instead of direct debit, and paying by writing an anti-nuclear request in the communication column. The receipt was also displayed. This second time, the walls were covered with lines.

The third exhibition is characterized by the placement of large “lines” not only posted on the walls but also suspended from lines across the exhibition room. When people move, the “lines” slightly sway, inviting visual and physical pleasure.

Although Michael Fried has rejected the idea that installation works can be transformed through the participation of the viewer, calling it “theatricality”, this is generally accepted in a positive light. Comparing Koyama's second and third exhibitions, the range of changes that occur when viewed is greater, and the theatricality is heightened. So, what is this theatricality?

Let me now correct the common sense that is prevalent in Japan regarding “minimal art”. Koyama's work can be classified as minimal art. Minimal art is considered in the Japanese art world to be unrelated to politics. It is often mentioned and praised only in terms of formalism and modernism. On the other hand, installation works with themes and narratives that have increased since the 1990s are viewed with disdain by formalists and modernists as "impure" because they refer to the outside of the work and often have political themes. It was done.

In fact, in recent years overseas, it has been argued that minimal art artists were involved in political movements, specifically the anti-war movement of the 1970s. Several critics have also interpreted the work itself politically. Let me summarize my analysis of Carl Andre and Donald Judd's works and introduce only the main points. Using materials that they do not process has the effect of reducing capitalist utility. Furthermore, by arranging minimal materials in the same way, hierarchy is denied. A lack of explicit theme, subject matter, or message often distracts from the implications, but there are also examples, such as Dan Flavin, where the argument is more explicit.

Koyama is also involved in raising issues and supporting activities related to Chechnya, Ukraine, and Palestine. In terms of political activities within the category of art, there is a project in which he played a central role, the “Declaration of the End of the Olympic Games Exhibition”.

Koyama’s “Line” work has two intentions. First, he contrasts meaningless production (labour) with meaninglessness. It is also about expressing individuality through repetitive and regular work. Minimalism generally seems to be the embodiment of capitalism and industrialism. However, if we view art and expression as a process rather than a result, there is a levelling and reduction. At that time, what should have been a meaningless act will take on meaning. It is a dilemma of utilitarianism, where a meaningless act ends up being meaningful.

And individuality is imprinted in the uncertainty of the angle and spacing of the lines. Added to this uncertainty is the visual dazzle of repeatability. Additionally, as the viewer moves, airflow is created, causing the work to sway. Everything is not fixed and objective, but relative and subjective. It only arises from mutual relationships.

The state of this work is related to the political movement and political art movement that Koyama is involved in. Koyama describes his intention to create his work as “envelopment”. Enveloping means dividing, delineating, and enclosing. He uses this against the establishment. Because he uses a minimalistic method, his works do not have the sublimity of a larger story. The encirclement and confrontation that he refers to does not end with minimal ‘individuals”.

This is because there is a theatricality, or relationship, between the work and the observer, which is the most public form of expression.

Precisely because an act is minimal, it is also anarchy, and it also creates solidarity. This is also because minimalism embodies a “minimal autonomy” that denies hierarchy. Herein lies the possibility of Koyama's work “Small Acts of Resistance”.

ミニマルであることの政治性 戸山恢論

アライ=ヒロユキ 美術・文化社会批評

ミニマリストの戸山恢の表現と活動を知ることにいまどのような意味があるだろうか。

戸山の最新の個展はトキ・アートスペースでの2024年1月23日から2月4日にかけて開かれた「小さな抵抗」だ。これは2021年から同じ題名で展開されている個展で、本年は3回目。展示にも継続性があり、《線》と名付けられた作品が構成の主要をなす。

この《線》は雁皮紙が支持体。等間隔に引かれた線が画面を稠密に埋め尽くす。機械的に線描されたものでなく定規を使って描かれ、そのためわずかに揺らぎ、つまりズレがある。そのことが視覚的な快楽にとどまらない身体感覚の心地よさを見る側に与える。これは打ち込み、電子音楽が純粋な規則パターンでなく、微妙な揺らぎをリズムに持たせることで、聴くものになじむような心地よさを与えているのと同じ原理だ。

《線》は雁皮紙にカーボン紙をはさんで1/4に折り、上からペン書きして線を転写することで生まれる。線は青、黒、赤の3種類。まとまった制作の時間と空間が取りにくい日常から生まれた手法という。作品には文字通り、戸山の日常が刻印されている。

三連の個展の展示構成を見ると変化がある。初回はそれまで取り組んでいた平面(基本的に小品)も織り交ぜられ、2回目からは《線》がほぼ主体をなす。「ほぼ」と書いたのは、戸山が以前から取り組んでいる「電気代一時支払いプロジェクト」、具体的には東京電力の電気料金を口座引落でなく毎月の支払いに切り替え、通信欄に反原発の要請を書き込んで払うものだが、その受領書も展示された。この2回目では壁面に《線》が敷き詰められた。

3回目のほうは、壁面への貼り出しだけでなく、展示室を横断するように線に吊り下げられた大きめの《線》が配置されているのが特徴。人が動くことでわずかに「線」が揺らぎ、そのことで視覚的、身体的快楽へと誘う。

マイケル・フリードはインスタレーション作品が見る側の参与によって変容する体験のありようを「演劇性」として忌避したが、これはむしろ一般には肯定的に受け止められている。戸山の2回目と3回目の展示を比べると、視ることによる変化の幅が大きくなっており、演劇性が高まっている。では、この演劇性とはどのようなものだろうか。

ここで「ミニマルアート」について日本に蔓延している常識を訂正しておこう。戸山の作品はミニマルアートに分類されるであろうが、これは「政治性」と無縁のものと日本の美術界では考えられている。フォーマリズム、モダニズムの点からのみ言及され、称揚されることが多い。これに対し、1990年代以降に増えた主題や物語性を持つインスタレーション作品は作品の外部への参照である、しばしば政治的な主題を持つ、としてフォーマリスト、モダニストからは「不純」なものと蔑視された。

実は近年海外では、ミニマルアートの作家は政治的な運動、具体的には1970年代の反戦運動に関わっていたことが論じられている。作品そのものの政治的読解も複数の批評家によってなされている。カール・アンドレとドナルド・ジャッドの作品の分析をかいつまんで要点だけ紹介すると、加工しない素材の使用は資本主義的な功利性を還元してしまう効果を持つこと、ミニマルな素材が同じように並ぶことによるヒエラルキーの否定があげられる。テーマや主題、メッセージが明示的でないことは往々にして含意から人の眼をそらさせるが、より主張が明示的なダン・フレイヴィンのような例もある。

戸山もチェチェンやウクライナ、パレスチナに冠する問題提起や支援の活動に関わっている。美術の範疇の政治的活動では中心となったプロジェクト「オリンピック終息宣言展」がある。

戸山の《線》の作品にはふたつの意図がある。まず有意味に対し無為・無意味の制作(労働)を対置させること。そして、反復と規則性の作業からにじみ出る個性である。ミニマルは一般に資本主義、工業主義の体現のように見えるが、美術や表現を結果でなくプロセスで捉えるなら、そこには平準化と還元が存在し、無意味であったはずのものに有意味が生じる。結果こそが有意味という功利性の顚倒である。

そしてブレには個人性が刻印される。このブレは、反復性による眩惑がつきまとう以上、また移動によって生じる空気による揺動もあり、固定的、客体的ではなく、相対的、主観的でもある。それは相互の関係性で初めて生まれる。

この作品のありようは、戸山が取り組んでいる政治運動や政治的美術運動と関連性がある。戸山は自作の意図を「包絡」と説明する。包絡とは、区分け、線引きして囲むこと。彼はこれを権力に対し用いる。ミニマルな手法だからこそ、大きな物語のような崇高性に回収されない。そして彼のいう包囲や対峙はミニマルな「個」のみで孤絶するものではない。それは見るものとの間に、表現のなかでもっとも公共性が高いという演劇性、あるいは関係性が生じているからだ。

ミニマルであるからこそアナーキーでもあり、連帯も生まれる。それはミニマルがヒエラルキーを否定した「最小限の自治」を胚胎しているからでもある。ここに戸山恢の作品「小さな抵抗」の可能性がある。