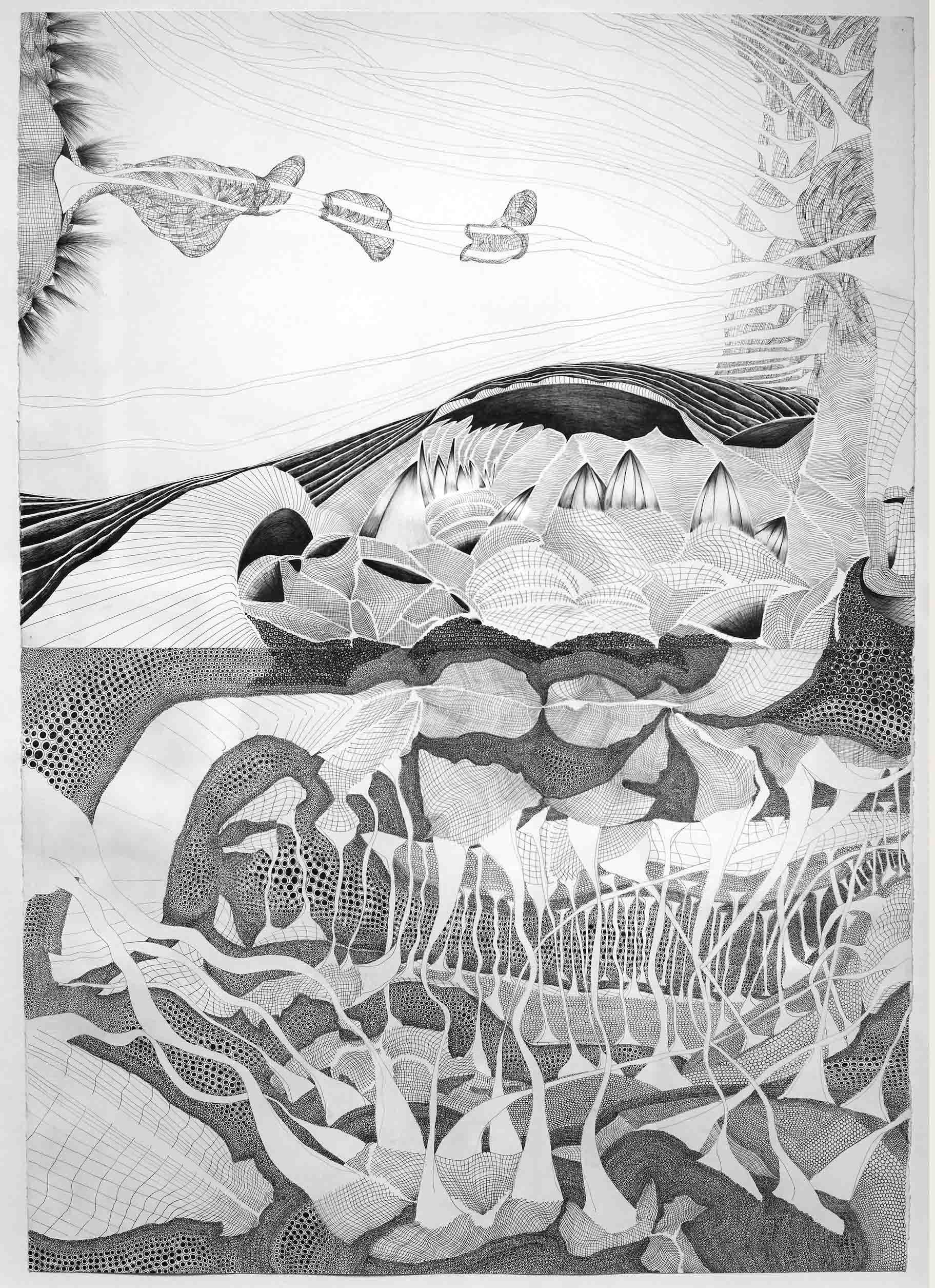

Ron Adams, Making a Mould for a Mountain, 1998-2022, ink on paper, 112 x 84 cm

In Making a Mould for a Mountain, Ron Adams presents a series of ink drawings informed by the surrealist tradition of Automatic Drawing in which a spontaneous and unpremeditated approach to line and rendering reveals latent imagery.

Surrealist artists believed that automatic drawing allowed them to access the intuitive or irrational aspects of their creativity, providing a direct link to the world of dreams and the unconscious.

In this exhibition Adams brings together automatic drawings spanning 20 years, showing the multifaceted foundation of an abstract practice concerned with signs, symbols and word play.

An Interview with Ron Adams

Melinda Reid

I sat down for a cup of tea and conversation with the Australian artist Ron Adams in October of 2023. We spoke about a collection of automatic drawings he produced between 1995-2019 that are being exhibited in Making a Mould for a Mountain at DRAW Space. This is the first time these drawings have been exhibited. The exhibition at DRAW Space coincides with a sister show – Lettuce Gyoza at Schmick Contemporary – of Adams’ surrealist paintings from the same period.

This exhibition brings together automatic drawings produced between 1995-2019. When did you first begin to experiment with automatic drawing?

I first started experimental drawing when I was a young teenager, maybe 12 or 13, just with a packet of textas. I used to like the idea of making marks and turning them into patterns and then becoming almost like acrobatic figures. Then, as I got older, they had more shading, but they were always created without necessarily having any future vision for them – they just had to become a shape, or a ‘something,’ a blob, or what I would call a biomorphic shape these days.

What did you call your drawing practice before you encountered the term automatic drawing?

I would have, I suppose, termed it doodling, but I wouldn’t have felt that ‘doodling’ was a big enough word for it. The ‘automatic drawing’ would have come out of my early twenties, late teens.

In 1924, André Breton famously aligned Surrealism with “psychic automatism in its pure state” – or in other words, expressions of one’s inner impulses, dreams, and chance associations. For surrealists, this practice has been a way of accessing what Freud and many other psychoanalysts have called ‘the unconscious.’ What do you believe automatic drawing gives you access to?

Well, I’m a big time dreamer, and I’m very good at remembering my dreams. I can even put them together like a mini-series. A lot of the early surrealist work I did turned towards almost erotic sexualisation. I suppose that was my youth, and being young and horny. That was in there. I was very interested in these beautiful, luscious, round shapes, and how they would fix together, and how sexuality could work in a different way. A lot of James Gleeson’s early work was very sexual, with a lot of male and female naked figures which weren't so much surrealist – they were more realistic on top of his surrealist landscapes. I became very interested in Freud and I loved what Freud was saying about sexuality. It's probably a little bit wrong these days, but it was right for me at that period, and he became a big hero, and Jung too. So more than anything, it was about using drawing to turn those sexual urges and ideas into a kind of automatic primitive futurism.

How would you describe automatic primitive futurism?

An automatic sexualised eroticism, but all the surrealist paintings have that moment to them. They all have this sexual or cute or want-able or huggable [quality], like Japanese Pokémons in a way. On the other side of that, I really like animation and I love comics. The bold lines and the colour come from that as well. I read comics as a kid, and particularly science fiction comics. I love science fiction and fantasy. So, I was interested in things you might find in the Lord of the Rings hiding behind a bush, or Star Wars. I like the unusual and the unseen.

Many surrealist poets, like Louis Aragon for instance, approached automatism as a way of experimenting with writing as a method of thinking. In your practice, is drawing a method of thinking?

I think so. It forms rarely negative thoughts in my head. I’m a bit of a ‘glass half empty’ type person and I don’t like that. So, the drawing is all about being positive and making the shape wonderful, happy. And optimistic.

Each of your drawings seem to have their own introspective lingo or idiolect.

I think they have their own intellect, and dialect and language. And they also all look like they come from one family. Particularly in the early ones, they all look like they have come from the Forest of Id, or something. They have all been born in that way. They’re all born harmonious and can live together. When you see all of the drawings, they splinter off into all sorts of bizarre shapes, but there's quite a link to the way they are, and they feel, and they look.

Could you describe your process for finding the visual language of a drawing?

Everything. Colour, obviously, and I like negative space… Negative space is very important.

What is the appeal of negative space in your work?

I think negative space is overlooked. It’s a bit like people overlooking weeds in gardens. Weeds are just as nice as the plants. It’s an unusual choice, I realise, because people don't look at negative spaces, generally. Engineers and architects might. In general, people don’t.

Negative space is perhaps a little like the unconscious – a space that we are generally not aware of.

In a way it is. I play these mind games in my head. I used to suffer from migraines, and I got really bored with it. I read something – which might have been Freud-ish – which led me to imagine that I had a corridor my head and there was a door in the corridor with the letter M standing behind the door. M for Migraine. Now, if the door opens that, M was not allowed to come out. So, if it did come out and stated walking down the corridor, I would get a headache. But I learnt over about a period of a year to make that M stay behind the door. So that's a little bit like how the drawings were. I can see those things in my head already. I think most artists can do that. It’s like you’ve almost made the drawing in a way. They're all just sitting there waiting to be picked, or you have to make the effort to do it.

Do you see the drawings in your mind in their complete form as you are producing them, or is it little by little?

In some instances, yes, in the complete form, and then some of the bigger drawings, I don’t see the form, but I have this intention, as if I know where I'm going with it, what it has to look like. For instance, for one of the ink drop drawings where ink drops turn into pens and things – I knew it had to have that solidity before I actually executed it. Some of the singular drawings are just one continuous shape and I don’t stop until its finished.

Words and short phrases are included in the compositions of some of your drawings. Could you describe the role of text in your work?

In some instances, poetry. In others, it’s probably shouting at you. I want you to take notice – that’s why I’m putting a word here. Or, this is the way I feel about something. But also, on the other side of that, I really like the look of words, and I like putting words together in patterns and forming shapes with them. I did a series of works called Possible Buildings from Words where I made text works with words stacked on top of each other. There were L’s coming down, and M’s supporting other shapes, and so on. But they had to have a particular number of letters and look like architecture.

It draws attention to the ‘thingness’ of words.

Yes, and that it’s that looking at letters. The letter S, for example. It's a beautiful round thing that rolls around and then stands up again or sits the other way to become a different shape, and you still know it’s an S, whether its teething and simple, or if you join lots of them together and they become whatever they become. And I love putting O's on top of Y's – they become a beautiful shape. It doesn’t have to be an O or a Y then – it’s just a shape, like a bird-like, or an architectural shape. I spent a lot of time for my large text works really thinking about the right amount of letters, like the right amount of L’s for instance. Some take a year to put together.

This is the first time many of these drawings are being exhibited. Why exhibit them now, and why at DRAW Space?

I moved studios about four years ago and I started going through everything and thought, ‘these drawing are too good to be wasted sitting in the studio and should be seen.’ I put one into an art prize and won a significant art prize with it. Then more recently, I exhibited some surrealist work at Galerie Pompom, and my manager Samantha Ferris said the exhibition was very popular. So, I thought I’ll talk to Damian [Dillon] and get the [Schmick Contemporary] show up and running, and participate in the DRAW Space show with the surrealist drawings at the same time.

How has your drawing practice changed over the last 30 years?

A lot! For the very intricate fine drawings, I was using a 0.1 pen. These days, it’s done with a very considered scalpel. I would draw on masking tape, then cut out with a scalpel, but as a gestural drawing. I like cutting out complete circles just freehand, and then peeling it back, painting the surface or drawing on it, then adding layers and layers and layers to it. For the recent electronic drawing on the computer, I use a program on iPhoto where I can use lines to make squares or circles. They’re very simple and geometric.

Rounded, shapely forms seem to reappear especially frequently in your drawings. Is there something about circles that attracts you?

Squares are okay. Rectangles are okay. Triangles drive me nuts. Circles are brilliant. It’s just the continuous beauty of a circle. It could be a bit ‘Groundhog Day,’ but it could also be a very large circle. Walking the circumference of the planet would take you a little while! I’m also very interested in physics and astronomy. The idea of all those planets sitting up there floating around each other is very appealing. It also goes back to James Gleeson and a lot of his beautiful, round, ball-y shapes which he used to use a lot of.

You’ve mentioned James Gleeson a few times already, but could you talk a little more about the significance of his work for your practice?

I just thought he was incredible, genius, and that he really should have had more acknowledgement than he did get. I was first became aware of Gleeson very young – probably in my first year of high school. And I’m gay, and him being homosexual as well really made me think, ‘oh my god – I’m allowed to be all of that!’ The other one that got me when I was really young was Joan Miro because I thought ‘oh, I don't have to paint like Rembrandt! I can paint like Miro!’ But, Gleeson more so because of his bravado, the way he put the male nudes into the work, being outwardly homosexual… it was really, really amazing. I saw a series of his paintings when I was a very young teenager in an exhibition in the city. They were small oils. And I thought they were just magnificent. About twenty years ago, we went to a gallery in the Southern Highlands and one was for sale, and I bought it! The other artist of that time that really got me was Francis Bacon, who also had that curvy, round-y, homosexual thing as well. I like totally different things now, but it has to start somewhere, and Gleeson in particular was really significant. One thing though – when first saw Gleeson’s work, I was opposed to the male nude in some of his surreal landscapes. They are very surreal landscapes, but with very figurative, realistic male figures. I would think that it didn’t belong. But, I think subconsciously, it does actually belong. It belongs in many ways in that reality. It’s a little like the idea of a subconscious – why can't it sit in that landscape?

Do you feel that there are similar tensions in some of your drawings between things that feel as if they belong and things that do not?

Yes, I like that. I like the idea that there’s a possibility that these things could exist somewhere, and that those shapes are hidden somewhere inside. If you break a rock open, you’ve suddenly got all these shapes.

© Melinda Reid, 2023