A group exhibition presenting textiles and textile processes in terms of drawing. This group of emerging artists have in common not only textile-based practices but an interest in exploring the transcendent materiality of used and re-purposed textiles, once recomposed.

Used textiles, whether as clothing, domestic fabric, or mass-manufactured utility items, are laden with references; historical, cultural, and labour issues emerge alongside deeply personal histories of loss, comfort, even longing. In varied contemporary acts of recomposition, used textiles which have been discarded, gifted, found, or repurposed are cut up, sewn, printed upon, pieced, dyed, and ultimately re-imagined into new forms as artworks. As often happens with textiles, touch is inherent, and the works incorporate those traditional textile actions in innovative and unexpected presentations.

Drawing with threads is simply another method of marking, colouring, and composing. Drawing with used threads however situates these works within the nuanced context of complex and layered histories that cloth inevitably evokes. As a project it invites viewers to consider textile-based artwork as a form of drawing upon the past.

The exhibition will open on Thursday 7 December and run until Sunday 7 January.

The exhibition features the work of Rae Boggs, Jennifer Brady, Monika Cvitanovic, Mitch Davis, Clementine McIntosh, Francis Meow and Abby Murray.

Curated by Melinda Hunt and Lisa Pang.

Fundamentally, across cultures, we are wrapped in cloths from cradle to grave, and we know them intimately. In terms of art making then, textiles provide an arena where many cultural and personal narratives can unfold.

Lisa Pang, co-curator with Melinda Hunt

Exhibition events

Please join us for these free events in the gallery. Meet the artists, learn about their practices and make textile art. No experience necessary. Materials provided.

Stitching Circle with Monika – Saturday 23 December, 11am-4pm

Quilting Workshop with Rae – Saturday 6 January, 11am-4pm

Room Sheet

Please click the image to download a pdf copy of the room sheet.

Email info@drawspace.org to buy. We will put you in touch with the artist.

Exhibition Essay

Mixed Wash / Musings on the cloth

In a 10th-century textiles treatise, a humble piece of cloth once introduced itself, announcing its inherent usefulness as a functional domestic textile item in the most poetic way.

I am the mandīl of a lover who never stopped / Drying with me his eyes of their tears. /

Then he gave me as a present to his love / Who wipes with me the wine from his lips.[1]

This humble cloth, the mandīl – here, seemingly something between a napkin and a handkerchief - emphasizes its qualities of absorption.[2] A piece of plain cloth, probably of cotton or linen, laundered and folded, held or laid close to hand, its work is to soak up the tears and wine associated with powerful human emotions. A small material thing, unremarkable, yet a vital accompaniment to ritual, celebration, and crying. After use, to be washed and used again. Softening and transforming with every use and with each wash, the mandīl is anonymous, yet known to us all. In this exhibition Recompose / Drawing With Threads, seven artists explore 21st century equivalents of the 10th century mandīl, of cloth used over and over.

I am the cloth of quiet absorbance.

Jennifer Brady

Just like that 10th-century cloth, Jennifer Brady is drawn to the quietened qualities of absorbance, where the drawing in of marks into fabric bears witness to a muted form of expression. Here, in that dampened down space of stain-swollen fibres, she explores cloth in terms of sensation. Hers is a body of work gently exploring what she calls the aesthetics of softness as a language for often unspeakable experiences. Working from personal mental health experience and the ensuing social isolation, Brady started working with bedlinen - mattress protectors, sheets, and blankets. These were sourced from her family home and friends. Padded, white, and elasticated, these are the textiles that cover and surround our intimate resting place – the bedroom – alternately a place of sanctuary and escape, but also the dim setting for nocturnal wakefulness and rumination. These are the machine-manufactured textiles designed to absorb blood, sweat, ink, and other stains, the messy matter of being human. As a sheet of white drawing paper records a deliberate drawing of the hand, as a white sheet records a stain as non-deliberate drawings of the body.

Brady is drawn to depict in-between states, those liminal moments of thought - just before you fall asleep, when you have just finished crying, or when you are coming out of a season of anxiety or depression.[3] More than white and soft materials, Brady suggests a more overt language of liminality through text – repeated, looping, indirect and printed - to record inner ramblings within a soft and safe space. After all, bedding is the stuff of childhood forts, tents, and pillow fights.

I am the cloth of Silent Histories.

Abby Murray

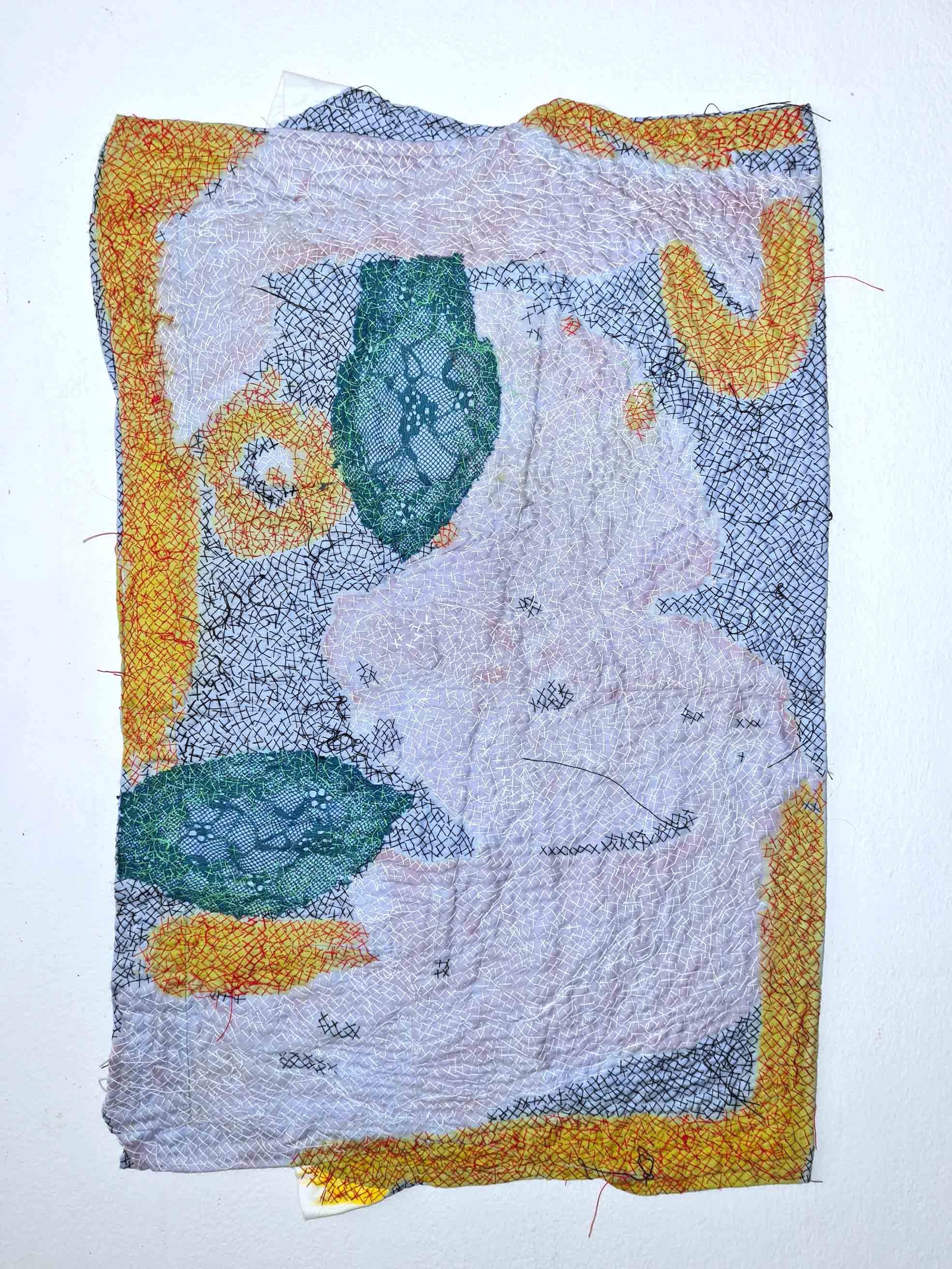

Abby Murray’s cross-disciplinary practice approaches textiles from many directions; and through a variety of mediums. The presence of different materialities creates a storm of surface activity, which paradoxically conceals while revealing what she terms their silent histories. Murray’s practice questions the methodology, discipline, and hierarchy of things, with works that at first glance defy categorisation while beckoning the curious. There is a looseness and deliberate lack of formal structure in the works, which are also vividly coloured and brimming with expressive marks. This conveys a certain precariousness; as though boundaries are breaking down, and things are slipping from one state to another.

Somewhere between quilting, textiles, stitching, painting, sculpture, and installation, an amalgamated articulation emerges. Re-assembled from found textiles, her own destroyed paintings and strengthened with bent wire, Murray’s pieces draw on personal stories, myths, and memories of place. The works sometimes resemble intelligible things in the world but at times merely suggest. ‘The Lake’ and ‘The Staircase’ aim to disobey the borders we place between drawing and sewing, exploring how a single stitch, a found material or a discarded painting can call into question how we understand and legitimise the fragmented, complex and multi-faceted aspects of our histories.[4] The staircase may take you there, unless you fall through its soft tread, deep into a remembered lake.

I am the cloth of functional abstraction.

Mitchell Davis

Sometimes the cloth is large enough to cover a person. Working at scale with mass-produced, frequently plastic textiles previously in use as tarpaulins, tents, bags, and blow-up mattresses, Mitch Davis explores their remnant functional history through pattern. Mass-manufactured, these objects of soft architecture, suggestive of temporary shelter, itinerant bedding, and travel, are paradoxically reconfigured through the traditional textile process of quilting. Taken apart by Davis and displayed pieced and flattened on a wall, with their geometric elements laid out in bright, often primary colours, curiously, they resemble hard-edged Modernist painting or contemporary echoes of the quilts of Gee’s bend. Occasionally this resemblance is deliberately and humorously manipulated through replica textile ‘paintings’, as Davis refers to his work as an exploration of non-traditional painting.[5] The artist David Sequeira on his own multi-disciplinarity recently commented on the capacity of colour and geometry to articulate complexities associated with the ‘unsaid’, clarifying the role of colour and geometry as wayposts to contemplation.

In Davis’ work, mark is obvious in the imposed pattern, derived from quilting patterns. Upon closer looking however the marks that come with the material betray its former use – the stripes, colour, text or degraded surface bringing with it a recognition of its transient state between industry and art. The journey from textile objects of unabashed functional brutality through to these composed geometric picture-quilts is for Davis a way of reconciling gendered notions of identity as cultural norm but also within himself. The transformation of textiles that would otherwise be disposed of, into items reassembled with care, to the hum of a sewing machine is a process offering comfort.

I am the cloth of generations.

Monika Cvitanovic

For Monika Cvitanovic cloth is at once textile and technique as she locates her practice within a close circle; the embodied inter-generational knowledge held and shared by women in her family. The passing down of knowledge is not purely how-to technical but also embraces an attitude of care towards cloth, clothing, and to each other. Cvitanovic conceptualises her use of needlework as a way of drawing attention to hidden labour, and in the context of textiles and the garment industry, this is a feminist commentary equally applicable to traditional hierarchies in the art world. She explains that by asserting a slow circular textiles practice as an antidote to neoliberal economies, I also explore repetitive free-form stitching as a method of self-care that rejects the patriarchal value of perfection.[6] This is particularly asserted in the presentation of her energetically stitched and buckled textile work, derived from clothing and which says so much about the human body, as wall-bound, the space traditionally reserved for painting.

The Remediation series sources recycled clothing remnants including men’s shirts and women’s underwear. These are brought together, made in a melange of domestic methodology; a veritable soup of free stitching, natural dyeing and recomposition of charged textile elements. The results are textile forms that writhe with a coiled and compressed bodily energy – of the people who wore them and of the artist who painstakingly stitched them.

I am the cloth exploring identity.

Rae Boggs

The mandīl can also be found among the awkward and the uncertain. There are times when the story, colour, clothes, and toys just don’t seem to fit. How do we come to recognise our identity when the seemingly innocent soft things, the textiles of our childhood don’t fit us? Rae Boggs’ expanded print, sculpture and installation-based practice is driven by their ongoing investigation, through textiles and its processes, into the mythology of tropes and gender stereotypes. Poignantly, their textile practice is based on clothing, toys, and quilts from their own family’s cast-offs. From these, Boggs has remade a material culture, suggesting a language that better fits their lived experience. The critique while gentle, and clothed so well, is effective. When we begin to learn language, we begin to learn to categorise and to designate. Boggs’ wry response to this is summed up within a title to a work, ‘Wearing my Pronouns on My Sleeve’.

The works themselves are of course appealing – cute, soft, funny, and playful things. Fashioned from the textiles of our collective cultural past, they seem familiar, a little wonky, just a bit out of shape and so benign. They conjure up what it is to be young and unformed, learning how to live and love. The soft stack of fabric cubes, the floral patches, the tartan patches, the rudimentary dolls, the furry edges and the quilts of many colours, they soften us, so we too feel the seductive pull of conformity. And yet, we all wish to and should belong. As many of the artists in this exhibition have commented while working to transform the materiality of recycled textiles into artworks, there is safety and comfort to be found in the soft fabric constructions so evocative of childhood.

I am the cloth of Place.

Clementine McIntosh

Connection to place, collaboration with local communities, and a commitment to circular economies underpin the practice of Clementine McIntosh. Moving beyond site-responsive installation alone, McIntosh works to source, make, and return textiles within an art practice that resembles more of an eco-system than the familiar commercial model of contemporary art. She describes how her process-based practice focuses on the act of mark-making to record local dialogues, exchanges and relationships connecting herself with others (strangers and/or the nonhuman).[7] The manner in which she sources textile materials is a commentary on barter systems operating within communities, callouts via social media groups, an opportunity at her gran’s nursing home, seasonal vegetation as dyestuff, and often, the kindness of strangers. McIntosh elaborates on the concepts of care and custodianship within her practice, as she transforms the otherwise discarded into the displayed. Afterwards, she ensures that the artworks are returned to nonlinear systems – sometimes gifted to others, repurposed, or even returned to earth as compost. The circulation is a calculated gesture, a rejection of the art market and an acknowledgement of the significance of place over the preservation of artefacts.

In an insight from another culture, compare the way McIntosh uses cloth to reference place to the cultivation of a path within a garden. It is said to be a conscious objective of the Japanese garden to establish in us a conscious dialogue between occupied and unoccupied space, between the act of doing and not-doing, and it is achieved by way of the garden path, dotted with prompts and obstacles to guide us towards a particular understanding.[8]

I am the cloth of clothing.

Francis Meow

Artist Francis Meow walks the walk, paying close attention to the prompts and obstacles along the way, observing textures, colours, sounds, and their evocation of feelings, memories, and images. This is the pattern of cloth and its relationship to us - we move about within cloth. We wear it daily as our second skin. Whether patching a jacket, making a brooch, drawing or painting, Meow describes his practice as walking mending and perhaps the source of his material is the perceptual experience, rather than the textiles or technique themselves.[9] So, in taking up a used and worn cloth and with needle and thread, mark by stitched mark, transforming it into new cloth the overwhelming gesture is not the skill or beauty evinced but the one of care.

When this futon cover came into my hands, already torn and worn beyond repair, the traces of neat laundering and careful folding filled me with an inexpressible sense of relief. The people of the house where it was used may have been poor, but they were not in any way wretched.[10]

The textile process of darning not only reinforces and strengthens a cloth but protects the wearer from cold. And yes, when visibly colourful it also decorates and celebrates.

Recompose / DRAWING WITH THREADS

In varied contemporary acts of recomposition, these seven artists transform previously used and worn cloth. Their materials derive from the discarded, gifted, found, or repurposed. In actions akin to drawing in their simplicity and directness they cut up, embroider, sew, print upon, piece, dye; ultimately re-imagining new forms from the old. As often happens with textiles, touch is inherent, and the works incorporate those traditional textile actions in innovative and unexpected presentations.

© Lisa Pang, November 2023

[1] Kitāb al-muwushā (Book of Brocade) by Muhammad al-Washshā in ‘Textile Terms: A Glossary’ (Edited by A Reineke, A Röhl, M Kaputstka, T Weddigen, 2017: Emsdetten, Berlin, 9.

[2] Interestingly, while that context defined a mandil as a napkin it can also mean, variously, a handkerchief, hand towel, tablecloth, a piece of cloth folded into a turban, worn over clothes as an apron, a small coat or even, a henpecked spouse. In all definitions the cloth is humbled.

[3] Jennifer Brady, Artist Statement, October 2023

[4] Abby Murray, Artist Statement, October 2023

[5] Mitchell Davis, Artist Statement, October 2023

[6] Monika Cvitanovic, Artist Statement, October 2023

[7] Clementine McIntosh, Artist Statement, October 2023

[8] Sophie Walker, The Japanese Garden, 2017: Phaidon Press, London, 35

[9] Francis Meow, Artist Statement, October 2023

[10] Borotachi no henreki (The Lives of Rags) by Horikiri Tatsuichi in Tanaka Yuko ‘The Power of the Weave: The Hidden Meanings of Cloth (Translated by G Harcourt), 2013:LTCB International Library Trust: Tokyo, 165.