Gary Warner / WORKING DRAWING

6pm Friday 8 September to 5pm Sunday 1 October 2023

Curated by Melinda Hunt

I heard the quiet dismantling sound.

Akari Fujise, Signals #22, drawingtube.org, 2021

I feel the marks do that in a way… you can almost hear them.

Julie Mehretu, Modern Art Notes, 2013

A text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination.

Roland Barthes, The Death of the Author, 1977

The prepared piano now has a life of its own.

John Cage, Empty Words, 1973

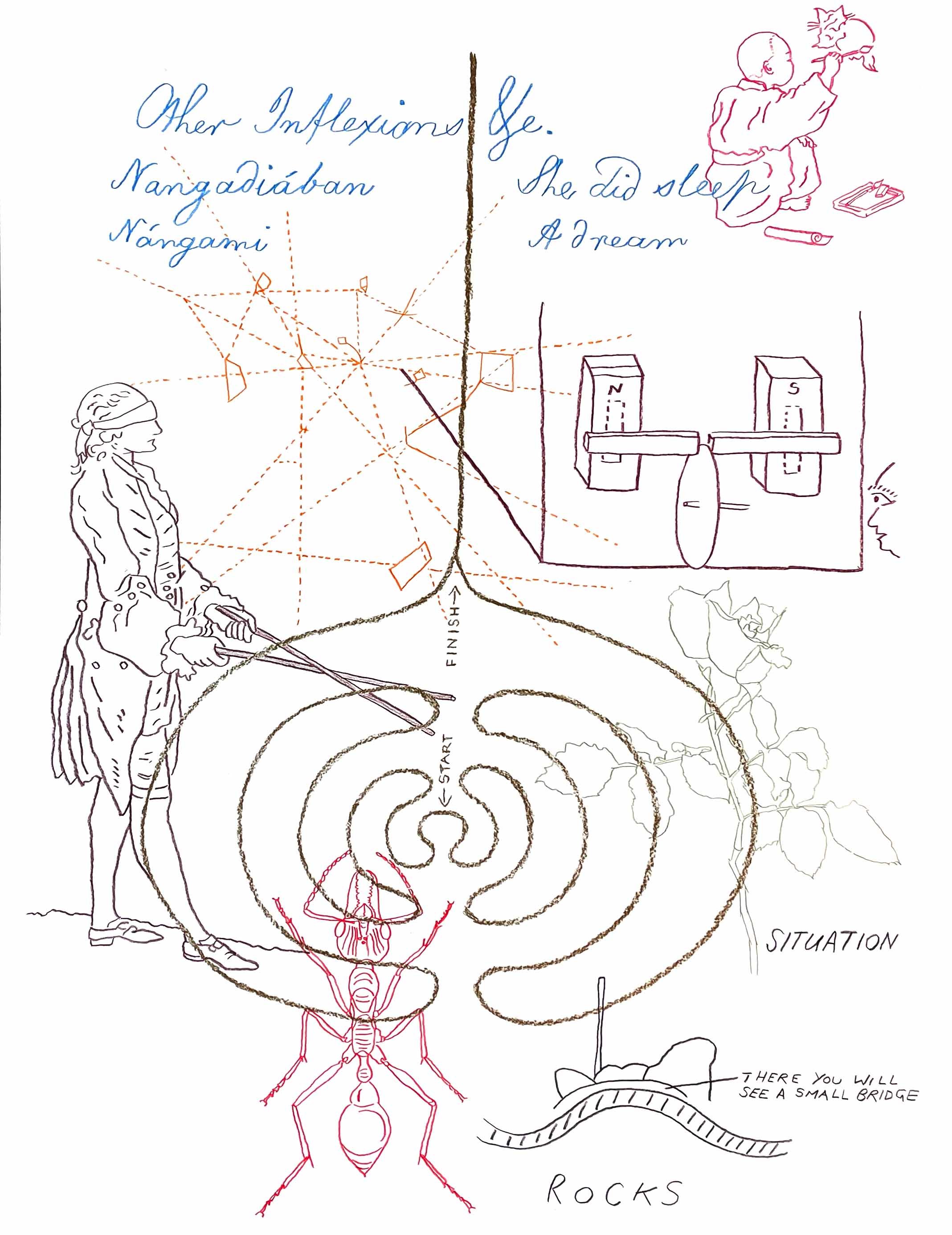

IMAGE: Gary Warner, 15 sampler drawings (detail), 2023,

colour pencil on drawing paper, each 60 x 81cm

Image courtesy of the artist

Gary Warner’s drawing practice is fluid, polymorphic, continuously unfolding through making, thinking, feeling, listening, observing, touching, absorbing, teaching, responding, working, drawing. Warner has abiding interests in in the sonic and performative aspects of drawing as much as the visual and has long explored potentials of autonomous mechanical drawing machines and systems of mark-making.

This exhibition at DRAW Space provides an opportunity to bring some of the products, processes and interests of Warner’s practice into the social space of contemporary art where, ideally, each visitor performs subjective acts of engagement and response.

The artist will occupy the gallery during opening hours - making new drawings, having conversations, creating soundscapes, and experimenting with the possibilities and specificities of the space. Events will be staged each Sunday afternoon.

“You are invited to be your own lamp.”

Gary Warner

Sunday afternoon events

September Sunday 10

the Sensilab drawbots

drawing by the Sensilab drawbots

+ conversation in-gallery with Professor Jon McCormack 2-3pm

September Sunday 17

amplified musicalities

sound + drawing durational performance with drawing machines, Cosmos + RoAT

October Sunday 01

finissage showing works generated during exhibition

Works in the exhibition

two lines between floor and ceiling, 2023

15 sampler drawings, 2023

sound drawing for DRAW Space and John Cage, 2023

demonstration model - a Sierpiński gasket, 2023

drum drawing [staccato], 2020

object that explains itself, 2014

mindless drawing, 2023

dialectic situations between various drawing machines, 2023

codebook (video), 2022-23

Professor Jon McCormack in conversation with Gary Warner

A conversation about the intersections of drawing and computing between Professor Jon McCormack, artist and Director of Sensilab, Monash University and Gary Warner. Jon is the founder and Director of Sensilab at Monash University, a research lab based on the idea that the best way to learn is by making things. Three of Jon’s Sensilab drawbots will be making autonomous drawings in the gallery, he will demonstrate his recently developed Noise Drawing software, and talk about AI and creativity.

Room Sheet, About this Exhibition

Click the image to the left to download a pdf copy of the the Room Sheet and information about the exhibition.

Works in the exhibition, the artist’s notes

two lines between floor and ceiling

An exploration of referent and representation developed in response to DRAW Space’s generous floor-to-ceiling distance.

A string of handmade aluminium beads hangs from the ceiling near the full-height street-facing windows. Each small monochrome element is hand-cut and folded from emptied craft beer tins. The sequence is a chromatic sampler of industrial paint colours originally selected for brand differentiation.

Compelled by an invisible force, the long dashed line restlessly dances above a gleaming disc on the floor. A tall, thin drawing hangs on the wall adjacent to this agitated material register. Also spanning ceiling to floor, rendered in colour pencil on heavy drawing paper, it is a schematic abstraction of the animated string suspended in the realm of ideation.

aluminium, linen thread, magnets, 3600mm length; colour pencil on 220gsm Lana paper, 70mm x 3600mm

15 sampler drawings

The diagrammatic line drawing is an inference device creating a charged context for slippage between the intention of an absent sender (one who draws a drawing) and the deduction of a present receiver (one who perceives the drawing).

The line drawings of 15 sampler drawings, with their skeletal character and compositional crowding, explore an oscillation between the gravitas of representation - the relatively stable sign - and a provisional fluttering of reference - the fluctuating signal.

Reaching across and into diverse timescapes, cultural framings and modes of intellect, the grid of drawings manifests an imagistic energy store analogous to the sampling culture of music, film and art that were my milieu as a young artist in the 1970s and 80s. Differentiated by colour and intruding upon each other through proximity and overlap, this skein of delineated image objects invokes a field of open connective potential.

Hovering slightly above a bare reductive minimum, made with the anachronistic medium of colour pencil, the tangled tracery activates an associative cascade effect as the receiver’s eyes move across the surface, identifying individual elements against the interlocutory noise of the encompassing field.

15 drawings, colour pencil on cartridge paper, each 840mm x 600mm

sound drawing for DRAW Space and John Cage

The prepared piano now has a life of its own.

John Cage, Empty Words 1973

John Cage was born 111 years ago on September 5, 1912. While not alone in exploring the creative potentials of chance operations and actively addressing questions about what music might be, he was uncannily prolific, and his influence across art forms wide-ranging. I made this work in homage to his life, work and ideas.

It is constructed from reworked post-consumer packaging, primarily plastic, cardboard and aluminium, formed into channels, tunnels, chutes and drops arranged in site-specific marble-run slaloms. A visitor climbs a platform ladder to drop quandong* nuts into open-mouthed receptacles. The wooden marbles sequentially sonify the various materials as they roll, zig-zag, drop and bounce along their gravity-assisted journey to terminal receptacles on the gallery floor.

Both visual score and sounding instrument, each slalom is an analogue sound sequencer creating a replicable noise-melody. While repetitive of the same sequence, each tumbling quandong ‘run’ varies depending on initial conditions and the momentary physics of material encounters along the way.

The woody spherical quandong nut works well for sounding because of its gyrified surface texture, similar in form to the enfolded surface of the human brain. The spatialised sonic lines produced by the kinetic action of the quandong nuts moving quickly through space and time are sound drawings.

*Derived from the Wiradjuri language, quandong is now a common name for many species of endemic Australian trees, mainly in the Santalum and Elaeocarpus genera. The nuts used in this work are sourced from Santalum acuminatum - the desert quandong - a small hemiparasitic tree endemic to Australia’s arid interior ecologies. Its fruit is a small, hard, woody nut surrounded by a bright red, thin, fleshy membrane that is good eating for humans and animals such as wandering emus that distribute ingested nuts in their scats. The nut’s journey through the emu’s body and the pile of fertiliser it ends up in are crucial to the germination and distribution of the species.

platform ladder, quandong nuts, re-worked post-consumer waste - aluminium, plastic, cardboard. dimensions variable

demonstration model - a Sierpiński gasket

Wacław Sierpiński (1882-1969) was a prolific, influential Polish mathematician and number theorist. This work explores an aesthetic potential of a form named for him, though it was present in various cultures before his mathematical description.

Primary geometric forms are central to the visual encodings of many traditional and First Nations cultures worldwide. They are also significant arenas of interest for artists exploring geometric abstraction, minimalism, non-objective and colour field genres.

Katsushika Hokusai encouraged aspiring artists of early 19th century Japan to visualise the world around them as combinations of rectangles, triangles, circles and arcs to assist in developing their abilities to draw and paint their world.

The Sierpiński gasket is a reductively simple yet confounding complex form that can be constructed in many ways. One method is to draw an equilateral triangle and a continuous line connecting each midpoint of its three sides to produce four triangles where there was previously one. Recursive repetition of this simple process - connecting the midpoints of all newly created triangles - progressively develops the ‘gasket’.

The successive triangles rapidly become too tiny to continue drawing into. Still, the possible recursion is infinite, and the resultant form is a fractal - an object-ideal that is self-similar across scales, meaning it will look the same regardless of magnification.

demonstration model - a Sierpiński gasket is constructed from 243 same-sized aluminium equilateral triangles hand-cut from craft beer tins. Each triangle has been worked with sandpaper and bears a drawing of a further iteration of the gasket that indicates the potential for infinite continuity and establishes a low-frequency oscillation between material and representation.

hand-cut aluminium (243 pieces), Posca pen, 3200 x 2700mm

object that explains itself

The Miura-ori is both an object and a method of folding a thin, flat material surface into a compact form of considerably smaller area. Japanese astrophysicist Kōryō Miura invented the fold in 1970 while working on methods to pack solar arrays for Japanese satellites. His knowledge of the Japanese craft tradition of origami informed his experiments.

An object that explains itself is a Miura-ori surface on which is drawn a series of diagrams illustrating how the fold is prepared. Co-opting this object-idea - the Miura-ori - into the context of art from its origins in the imaginative realms of physics and mathematics draws a line of homage between it and American artist Robert Morris’s 1961 Box with the sound of its own making, described on the MetMuseum website as “a manifesto of sorts: insofar as it makes evident the means and methods of its own production, it heralded a paradigm shift in art, one in which process, duration, provisionality, and incompletion take pride of place.”

graphite and ink on folded Dessin 200gsm paper, 1080mm x 750mm; photograph on 300gsm matte paper

drum drawing [staccato]

A silver rollerball pen is taped somewhat precariously to the end of a long, rigid, yet flexible thin steel rod. I held the rod and pen construction in one hand and sinusoidally flexed it against a drawing surface on the wooden floor of the 19th-century warehouse studio I occupied at the time.

The drawing was produced by walking around the paper, tapping the pen, exploring the physics of the ad-hoc assembly and discovering rhythms and methods of mark-making with the experimental drawing instrument.

An hour passed. A drawing emerged. A sound reverberates in memory.

silver ink on Fabriano 200gsm paper mounted on ragboard, 800mm x 800mm

mindless drawing

We think of drawing as an inherently human activity. Many other animals, objects and machines can make marks and patterns, but what differentiates mark-making from drawing? What might it mean for a non-human entity to learn to draw?

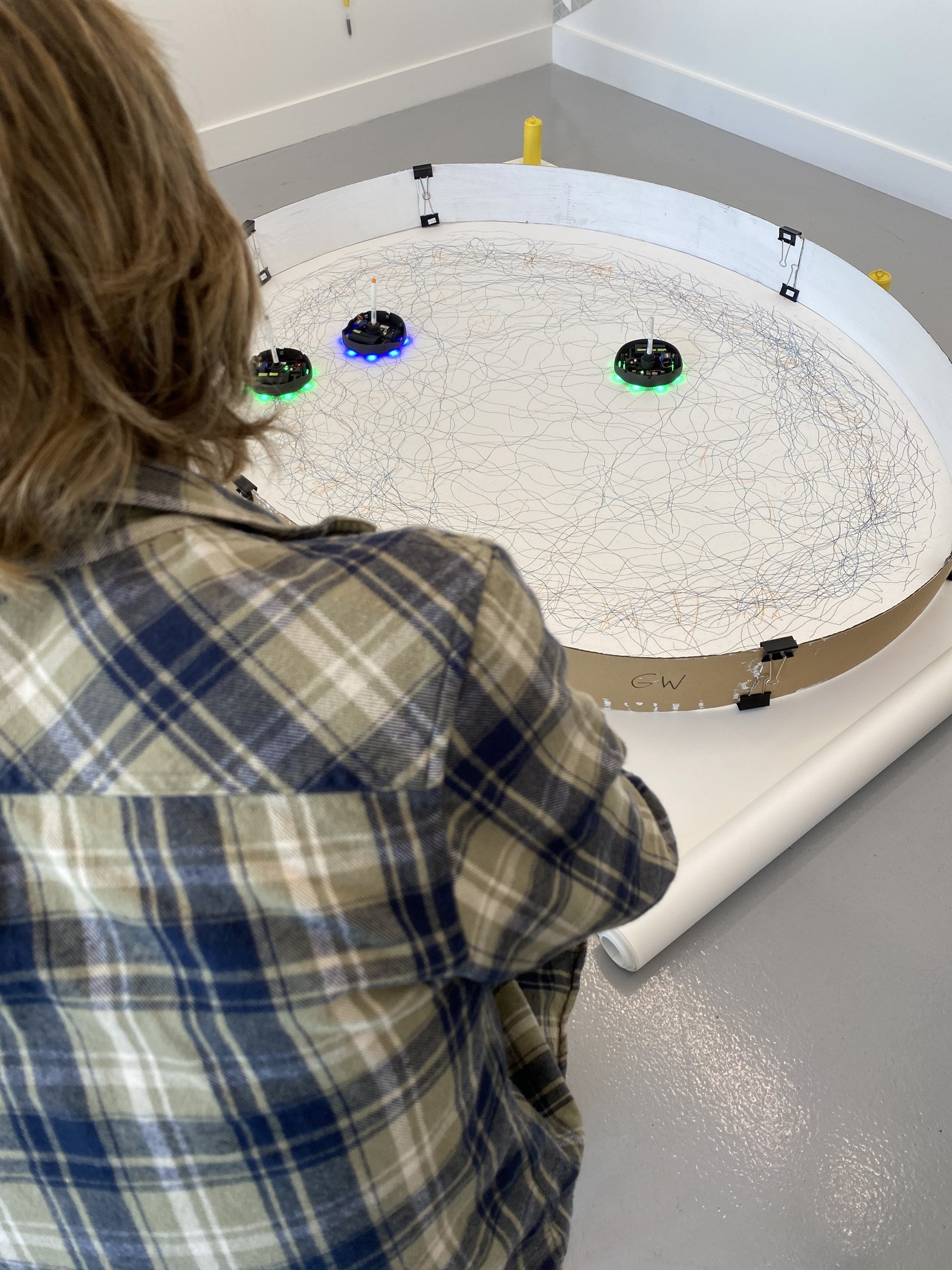

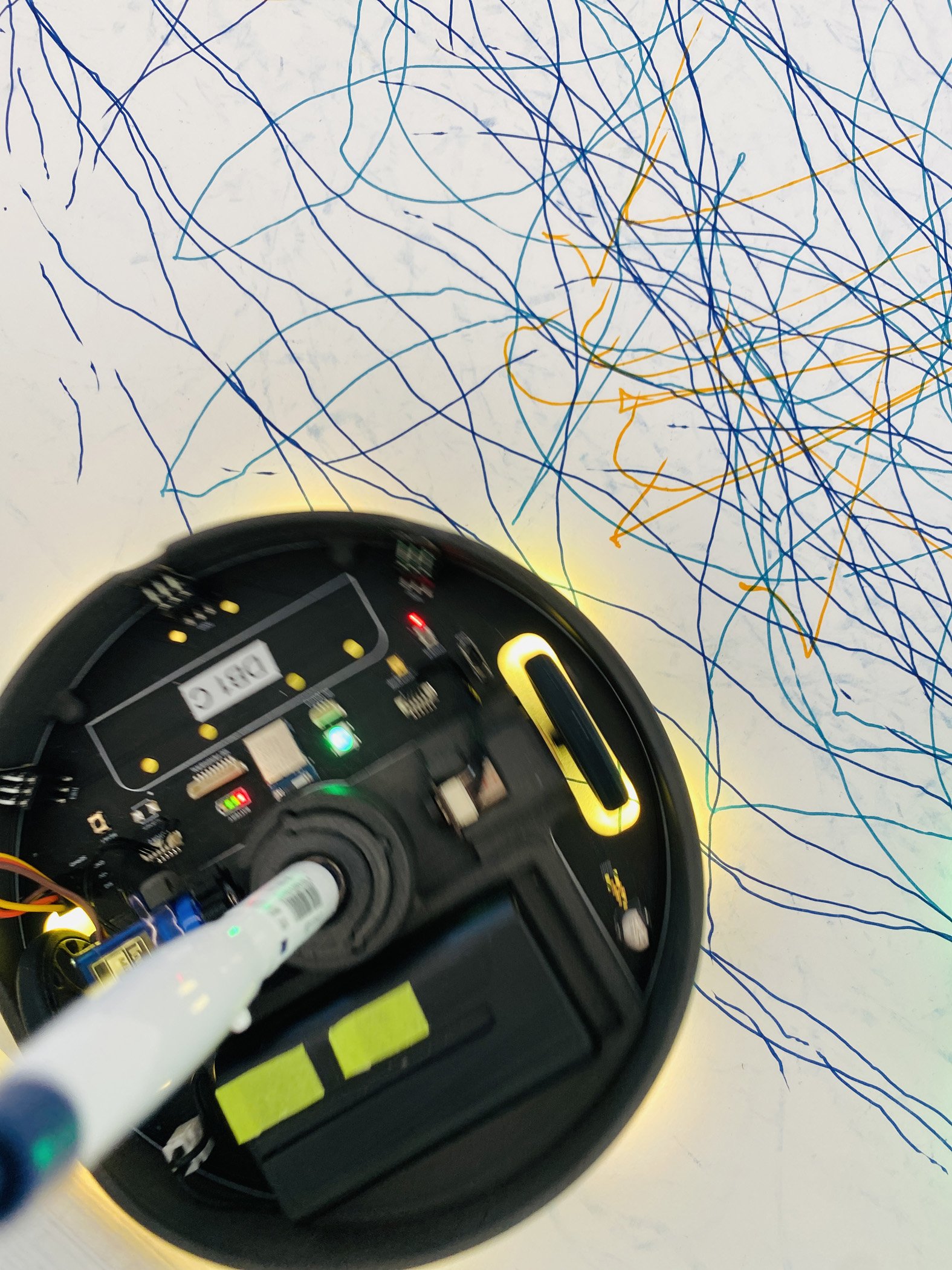

Sensilab drawbots are insect-like machines that can work cooperatively and exhibit collective and emergent behaviour by responding to their surroundings and each other's actions. Three with different operating instructions were sequentially activated in an oval arena to express their code for a while. Each drew with a different coloured Sharpie to identify the individual 'creators' variations in the final drawing.

Led by artist and computer scientist Professor Jon McCormack, a team at Monash University's Sensilab has been working for several years to develop the Sensilab Drawbot, a mobile robotic unit designed explicitly to create drawings with some sense of autonomy that might be convincingly argued as a form of machinic creativity.

Pioneering experiments inspire Sensilab's work in drawing robotics. These include works by the artist Leonel Moura, who uses autonomous machines to create art objects "indifferent to concerns about representation, essence or purpose."

Sharpie on Fabriano 200gsm drawing paper, 3600mm x 1850mm

Drawbots by Professor Jon McCormack and Elliot Wilson, Sensilab, Monash University. Situational context for drawing production by Gary Warner.

dialectic situations between various drawing machines

Drawings made by one drawing machine type are introduced to other types for additional inscription to create exploratory palimpsests that record displaced interactions between the mechanisms.

The sonic production of the drawing machines is periodically filtered and amplified live via a SOMA Cosmos Drifting Memory Station.

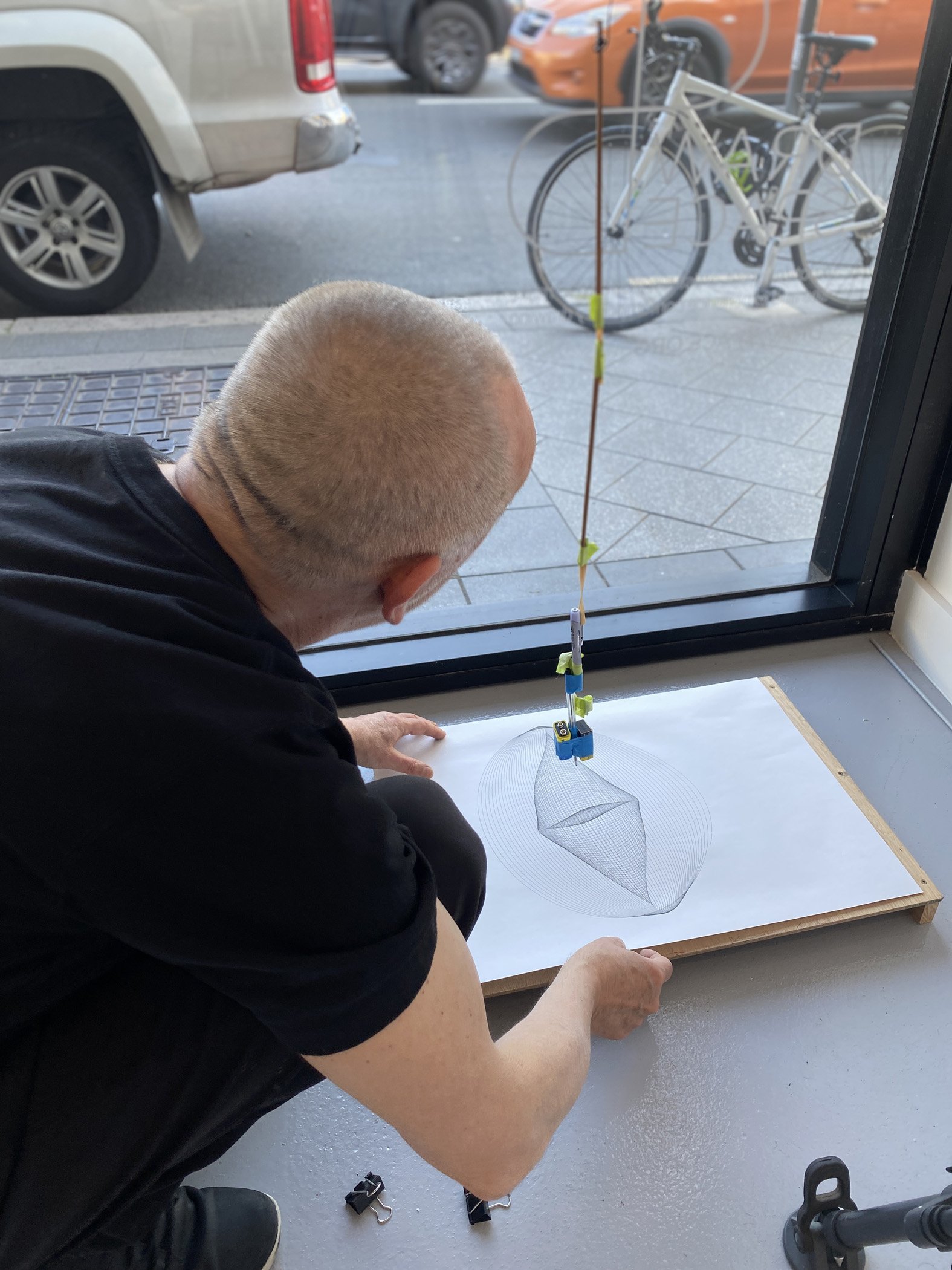

A 3-pendulum harmonograph dances a Newtonian choreography, a compulsive performance of process - gradually, evenly, expending energy transferred from a human body. Set in motion, left alone, the mechanical device cannot deviate from a unique path to stasis established by initial conditions. It is a drawing automaton - outwardly animated, inwardly inert - precise, unflinching, obedient.

Ad-hoc turntable drawing machines dance choreographies of chaos. Turning, turning, turning, their constructed bodies produce a romantic expressive projection. Though suspended within invisible bounding fields, each appears spontaneous, producing chaotic marks in evidence of compelling agency. They impose, intrude upon, the existential domain of human creativity. They are anxiety machines - outwardly animated, inwardly inert - deceptive, fascinating, becoming.

Sensilab drawbots dance choreographies of code, at once apriori constrained and autonomously responsive. Expressing software prepared for their calculating micro-circuits, these automata actively sense the immediate environment for certain changes and conditions that implement rapid shifts in wheel alignment and pen contact with the drawing surface. They are deduction machines - outwardly animated, inwardly reasoning - alert, responsive, unpredictable .

examples in exhibition: 5 x framed drawings, ink on A2 cartridge paper, 500x700mm (framed)

a 3-pendulum harmonograph

Originating in the mid-19th century, harmonographs are a type of Newtonian drawing machine or automata that translate the energy expenditure of free-swinging pendulums into complex geometric drawings. Harmonographs can utilise one, two, three or four pendulums in combinations of linear, rotational, singular or composite types. Each resulting harmonogram is a unique inscription of the harmonic relationship between the pendulums and a register of duration between initial motion and eventual stasis.

Each harmonogram is an unrepeatable outcome defined by the combination of infinitely variable initial conditions established at drawing commencement. These conditions include the length and weight of pendulums, their direction of movement, the degree of concord or discord of their frequencies, the type of pen and surface being inscribed, the amount of energy the human operator transfers from their body to the mechanism and so on. Incalculable combinations of even small changes in these conditions effect the drawing outcome.

Set in motion the harmonograph performs a graceful, mesmeric process of drawing production resulting in images of unusual precision.

formply, brass, timber, perspex, 18 x 1.25kg gym weights , 1200 (w) x 1200 (h) x 600 (d) mm

Harmonograph concept and design by Gary Warner; fabrication by Philip Sticklen.

chaotic drawing machines

I prepare various ad-hoc drawing machines based on a modified turntable raised above a drawing surface by an extendable tripod. The battery-powered turntable can be set to rotate at speeds from very slow to 45 revolutions per minute.

Combinations of rods, weights, springs and pens are fixed to the turntable and each unique chaotic assemblage will produce an unknown drawing outcome of expressive, often complex marks. Different pens offer signature mark types. Biro ink is sticky and messy; rollerball gel pens are finely calligraphic; felt tips offer osmotic blob soaks when the pen slows or stalls. Different papers and surfaces offer further exploratory potentials.

Allowed to perform for long durations, the machine’s drawings gradually build into detailed graphic recordings of aleatoric energies.

modified USB turntables, tripods, mixed media, dimensions variable

codebook

This work is a video compilation of my recent explorations in immaterial drawing. I use the artist-developed softwares Processing and TouchDesigner to generate animated abstractions that are effected and edited in the digital video software Final Cut Pro X.

Processing and TouchDesigner are interesting for different reasons, but share the trait of having user communities who offer libraries and examples of code that can be sampled, altered and reassembled to experiment with unknown outcomes, searching for developable zones of visual interest.

Each digital drawing in codebook is a brief scene underscored with experimental sounds generated using combinations of small synthesis and filtering modules. Some drawings are synchronous visual responses to the sound where the code is prepared to autonomously react to the audio signal. All scenes are rendered to monotone black and white, to foreground consideration of line, form and change.

The scenes are analogous to pages of a sketchbook, each separated from the next by a 60 second imageless duration intended to render the viewing experience discontinuous, antagonistic to commercial strategies of perpetual media flow. The passages of interstitial black provide visual silence, intentional passages of emptiness where viewers’ attentions can dwell upon what they have just hear and seen and/or shift back to the material artworks in the room.

1080p digital video, 56 minutes