Group show / AFTERGLOW

6pm Thursday 6 June to 5pm Sunday 30 June 2024

This June 2024, four artists experiment with light as an inscription of the invisible. Light is central to how we see our world, though often light itself, cannot be seen. The artists delve into hidden energies and vibrations to image time, the cosmos, sensory experience and spirit of place.

Curated by Amanda Solomons and Gary Warner, this show focuses on contemporary approaches to using light as a way to capture and retrace ethereal phenomena. Justine Roche ponders hauntology through the revelatory surfacing of historical events concealed in landscapes while Yvette Hamilton seeks to expose the unseeable radiance of celestial bodies and other occurrences.

Aidan Gageler makes works to be felt as much as seen, using antique processes of light, time, and chemistry. Sam James performatively draws with light to capture ghost-traces of movement and memory in public spaces.

Each reverts photography to its etymological foundation of the experimentation of ‘drawing with light’ and through this, revive and extend esoteric and anachronistic processes. The artists expand upon the hard-won effects of traditional drawing media - shimmer, glow, incandescence, lustre and radiance - through different techniques and technologies to create fascinating still and moving imagery that pictures the entanglements of light, existence and mind.

AFTERGLOW features the work of Aidan Gageler, Yvette Hamilton, Samuel James and Justine Roche.

“But the best early photographers evidently profited from their errors and learned, with surprising rapidity, to control (or at least to collaborate with) the refractory new medium. They also discovered a positive value in pictures that many would have called, and did call, mistakes.”

— Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, Photography, The London Quarterly Review 1857

Exhibition Essay

Gary Warner

Art is a welter of rhizomatous lineages, entangled ancestries of experiment, method, and intent. Photography began without the camera, its conventional symbiont, in the early 1700s. German polymath Johann Heinrich Schulze coated bottles with mixtures of chalk, nitric acid, and silver to determine and demonstrate his assertion that light, not only heat, could cause chemical reactions.

Over a century would pass before French and English experimenters created the first images we now identify as ‘photographs’ - light drawings. Since then, artists have carried the photo-aesthetic baton forward, prompting and incorporating technological innovations and inventing new methodologies for processes rendered anachronistic by technological succession.

AFTERGLOW presents contemporary artists Aidan Gageler, Yvette Hamilton and Justine Roche, who explore and expand aesthetic possibilities of some of photography’s earliest methods, and Sam James, who draws with light to create residual traceries of gesture. Each artist relies upon their individual senses of wonder, enquiry, invention, and experimentation to carry their work forward. Through their labours, they exercise their intention to exercise your inner life.

“The photosensitive layer.. is a tabula rasa where we can sketch with light in the same way that the painter works in a sovereign manner on the canvas with instruments of paint-brush and pigment...”

— László Moholy-Nagy, Photography is Creation with Light 1928

Samuel James says he’s always felt filming something to be a kind of theft, a taking from. Nothing other than the dubious partiality of a record is available to the subject.

He seeks to expand the relationship between filmed and filmmaker to become one closer to reciprocity.

Often working in the theatre, generating projected image media for spaces where actors’ bodies inhabit realms of evocation, Samuel finds the relationship between filmic image, living bodies, and the imaginary to be more synergetic, each enhancing and influencing the other’s reception by the audience who share the space.

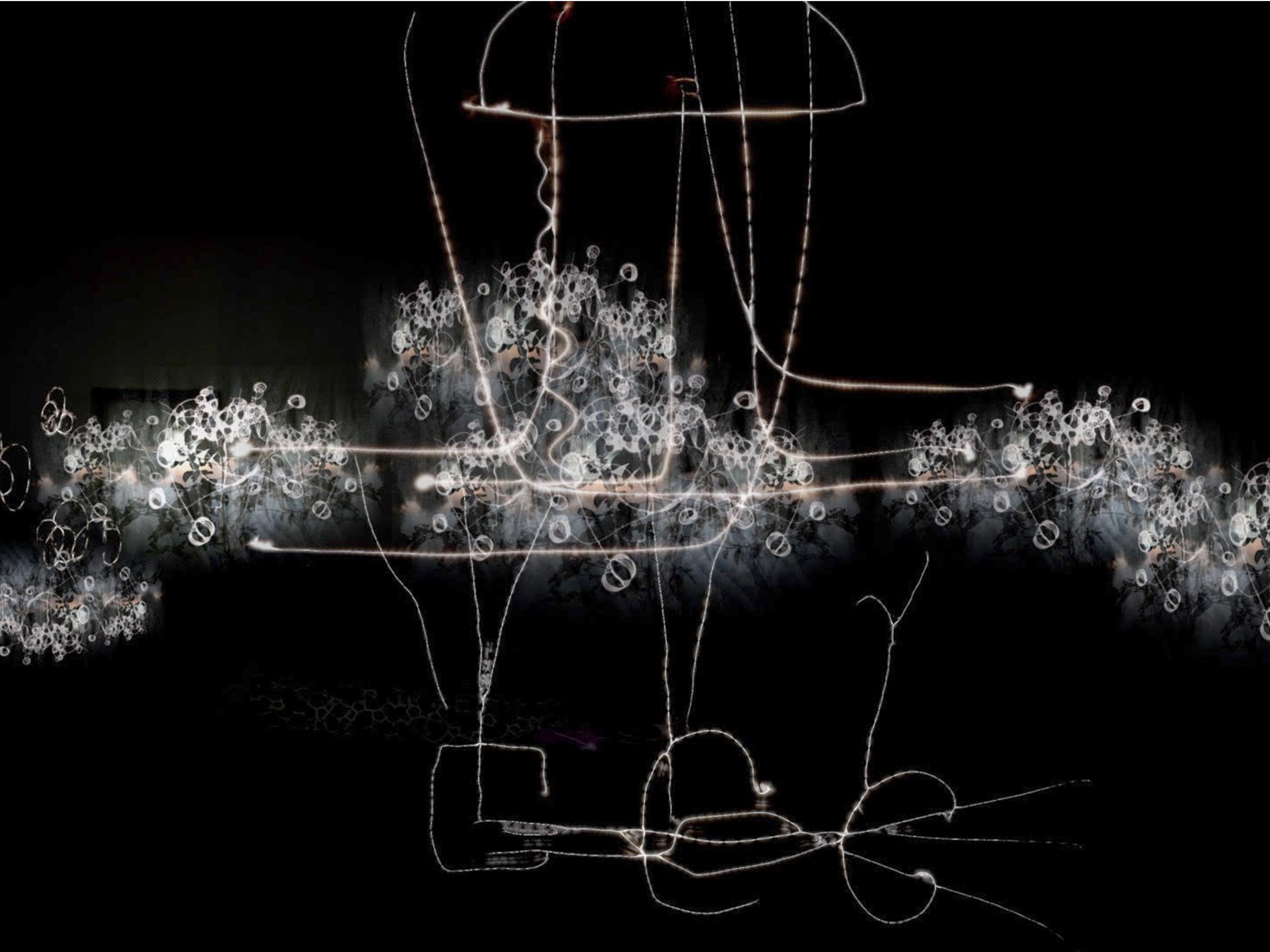

He migrates this dynamic into his performative investigations of place, becoming alone improvising actor translating subjective thought, feeling and memory into luminous traces of ephemeral bodily movement. We view him drawing in spectral silence onto nothingness with light, his body appearing and disappearing, foregrounding the apparitional disconnectedness of machine-imaging from embodied experience.

Now living in the Blue Mountains surrounded by World Heritage forest, for AFTERGLOW, Samuel returned to urban Newtown, where he spent formative years as a young artist, to explore memories of youth, milieu and place through phenomenological light drawing.

Each public location suggested or provided a symbolic motif to be repetitively drawn, upon and into the night. Now skilled in the esoteric practice of using cameras and a small handheld torch to produce bright yet ghostly gestural recordings, the artist shows us his technique through the performances. We witness the means of production to simultaneously understand ‘how it’s done’ and marvel at the revelatory becoming and open-endedness of each drawing.

There are many historical precedents, most famously perhaps Gjon Mili’s 1940s work with Picasso, or Man Ray’s 1930s ‘Space Writing’ series. In the 1920s, Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, husband and wife business partners, developed small hand-held and head-worn lights to record luminous traceries of people at work and play – typing, using drill presses, swinging golf clubs. Their interest was improving industrial productivity through analysing workers’ actions. The images they created for this most transactional of capitalist intentions retain a strangely resistant beauty that resonates with Sam James’ poetic contemporary enquiries.

“The photograph throws up the threshold as a possibility and a challenge, but do we ever really pass the threshold of the photograph - the moment, the artefact, the stillness - to reach that other place?”

— Nour Dados, Liminal Transformations: Folding the surface of the photograph 2021

Justine Roche uses various photographic methods, from familiar contemporary digital to mysterious ‘wet collodion’, a demanding 19th-century process involving a thin photosensitive film on a glass or metal substrate. Collodion is a syrupy solution of nitrocellulose, ether and alcohol, a sticky binder for photosensitive silver salts.

Collodion is prepared and poured evenly across a photographic plate (Justine uses 25cm square). The wet plate is bathed in a silver halide solution for a few minutes before being fitted in a holder, then a camera, and then exposed to light. The collodion and silver solution is most sensitive to blue and ultraviolet light ranges, which accounts, in part, for the strange visual quality of collodion-based imagery.

Once exposed, the plate has a developing solution poured across it, moving it to coat the surface as evenly as possible and watching the reaction to determine when to end the development phase. Then the plate, now an image, is rinsed, fixed, and thoroughly rinsed again, dried and varnished. Each stage of this artisanal process has degrees of unpredictability. Variations in chemical mixes, pouring techniques, vagaries of light play during long exposures, unintended inclusions of dust or contaminants – all can affect the resultant image. Justine explores and values this stochastic variability.

Many of the images selected for AFTERGLOW are from her various series investigating affective representations of place, with a particular interest in wetland habitats. She attempts to re-present moments of subjective sensorial intensity as epistemic image objects, offering viewers an open potential for personal associations. Many of her images oscillate in liminal spaces: between the indexical and the abstract – we can see something of the world in there and link it to embodied experiential knowledge but also feel mystified, uncertain, destabilised – and between typological expectations of drawing, photography, and painting. These oscillations energise the viewing experience, encouraging questions and speculation rather than providing answers and certainty.

“...make something out of nothing, in attempting which [the artist] must almost of necessity become poetical.”

— John Constable, personal correspondence 1824

Aidan Gageler is particularly interested in the potential for works of visual art to induce feeling rather than recognition. He uses combinations of photography’s archaic processes, ‘exhausted’ print papers and sheet film, and digital software to coax images from emptiness, to bring images into the world rather than to snatch them from it.

Online, he searches out recipes for photo processing chemistry and sources boxes of unwanted photo materials. For example, colour stock from the 1950s and, incredibly, photographic papers from the 1880s. Most of the boxes he eventually receives have been opened by previous owners and contain leftovers. In silence and complete darkness – no safelight – Aidan carefully opens each gift from the past. He uses his sense of touch to ascertain the contents and their condition before processing individual sheets in three successive trays of photo-chemistry.

The once-only process is blind, fuelled by anticipation, anxiety about the resource's limited nature, and an active imagining of time passed since the media’s original production and his activation of its image potential. Each packet has been exposed to its environment since first opened, and each resulting image, completely abstract, is nonetheless an index of time, place, and unknown narratives.

You will notice the presentation in unusual frames designed and made by the artist. This material exploration, which began as a gentle provocation to academic arguments about the violence of the frame, has become a valuable strategy of engagement that works to hold the viewer a little longer with each image object.

In Aidan’s carefully prepared and presented images, there is no viewpoint, no moment in time, no static position from which to view, no comforting sense of scalar relationship. These cognitive anchors are absent, and we are adrift, wondering, surmising, seeking a way to ameliorate the uneasiness of not knowing. Or responding to suggestive forms, beguiling colours and curious details from a place beyond language, from somewhere else within the complexity of self.

“Art is not an object of knowledge concerned with designing and representing; it is a kind of knowledge practised in a sensuous reality.”

— Elke Bippus, Artistic Experiments as Research 2013

Yvette Hamilton spends time outdoors watching sheets of photosensitive silver gelatin paper metamorphose from blankness to slowly changing images. She equates this durational engagement with the practice of drawing, where, similarly, a blank surface is acted upon to bring an image toward encounters with vision.

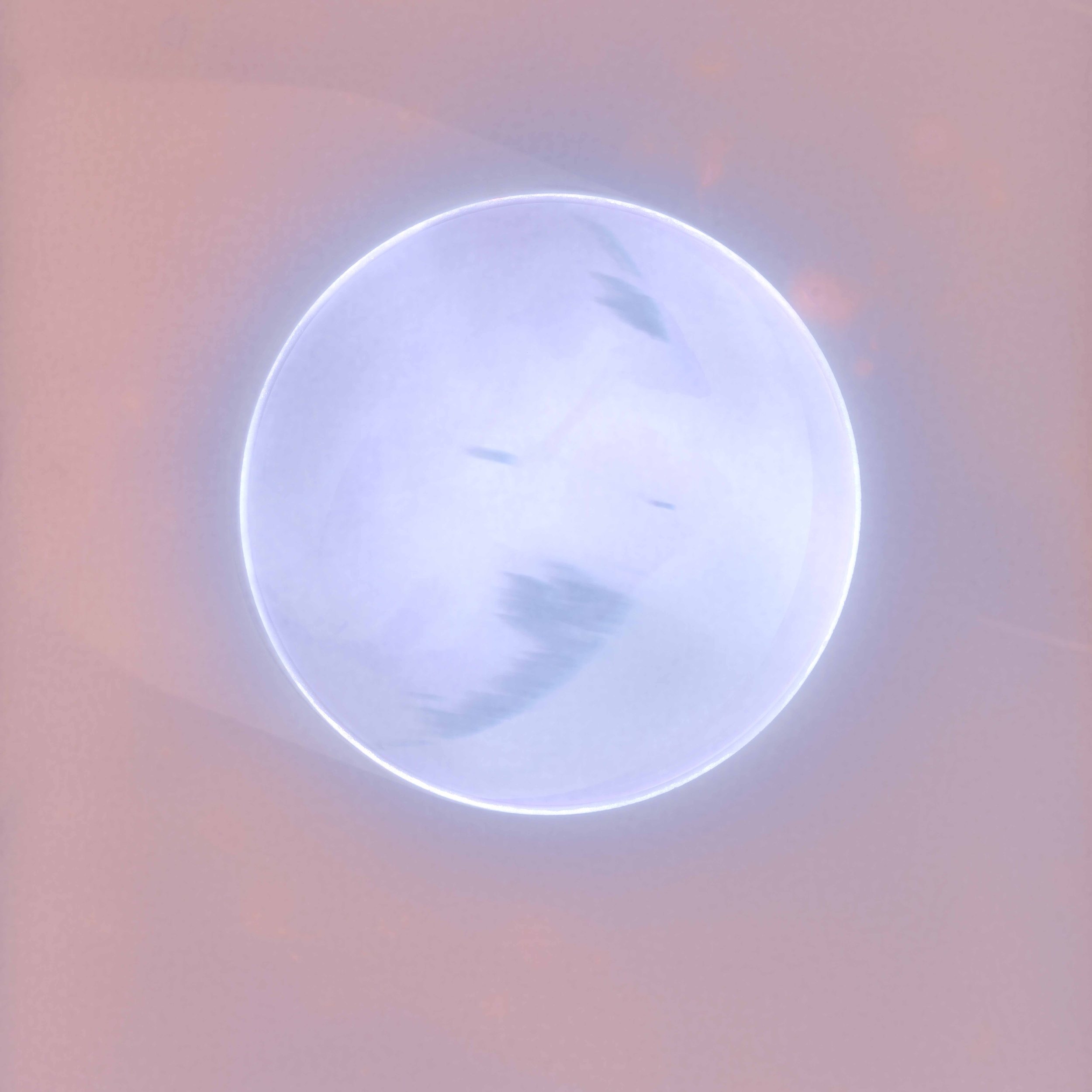

Her multipart work, Afterglow, shown here, was specifically created to explore correspondences between drawing and photography. A long line of white light-emitting diodes (LEDs) was used as an exposure source for photographic papers.

Some were processed to deep black lustre, others arrested along their drawn-out journey to darkness to capture abstract forms amid delicate gradations of pinks, yellows, and greys. The group is rearranged for each show. A fresh sheet of photo paper is placed under the LED line that arcs across a wall. It will be exposed for days to create a new abstract record of time, place and light.

Other works by Yvette in this exhibition are lumen prints created by exposing silver gelatin paper to sunlight. No camera, lens, chemical developer or fixative is used. Instead, the artist watches the paper changing – for 30 minutes to hours or days – and, at some point, seals the sheet into a lightproof bag. Next, a digital scanner (another type of camera) is used to copy-capture the image, a process analogous to the fixing stage of darkroom photography. The resulting scan is digitally printed, which affords the potential for scaling the image. The original sheet, returned to its lightproof container, remains in a state of potential photo-receptivity.

The 60 images of Yvette’s Solar Observation series of lumen prints were made at the Woodford Academy in the Blue Mountains in response to 1874 observations made there of a rare transit of Venus in front of the sun. Rain fell during much of her residency, but she nonetheless went outdoors to make her observations. Raindrops and other effects of inundation are evident in the images.

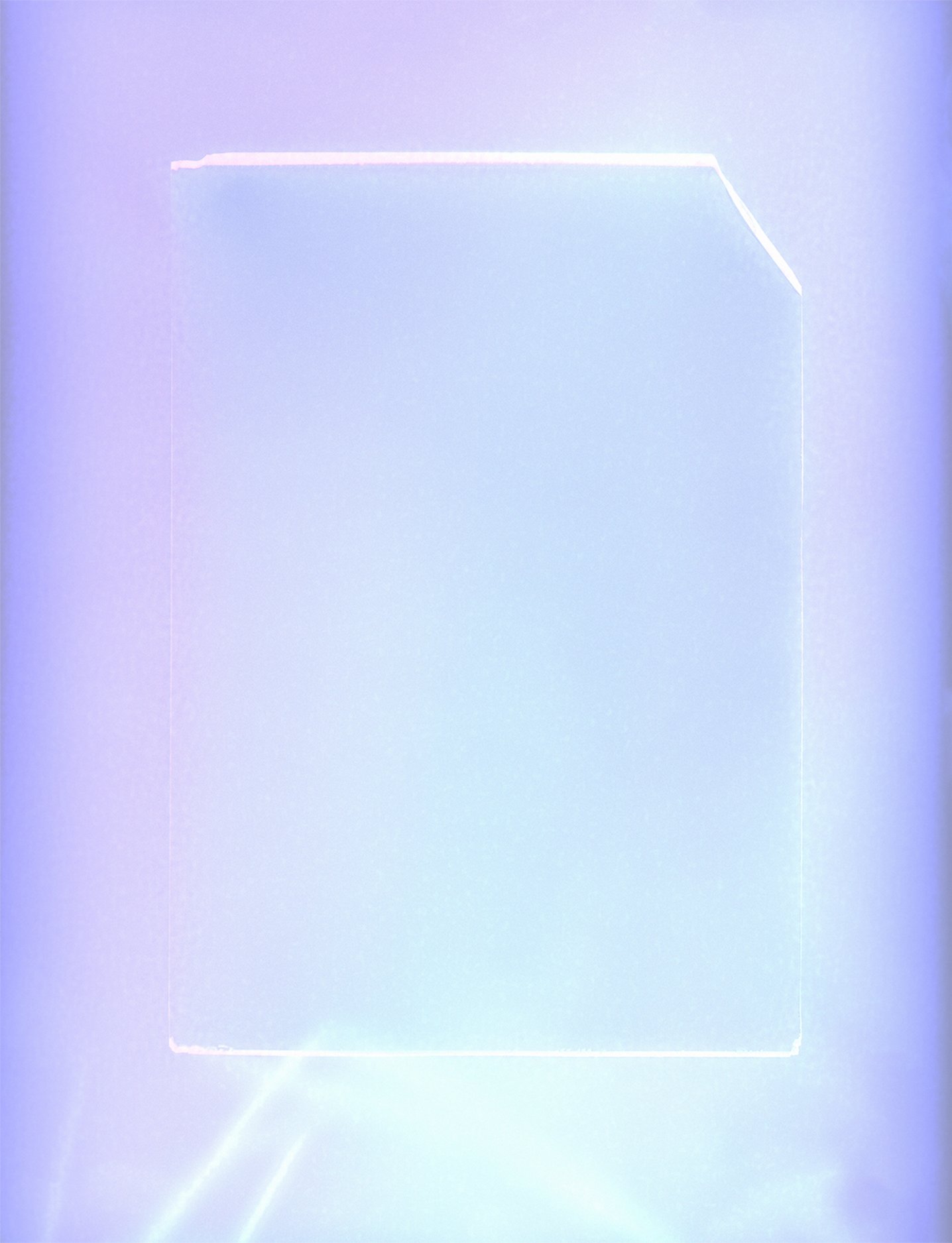

A current residency at the Linden Observatory, also in the Blue Mountains, continues her fascination with correlations between astronomy and photography. She uses pieces of glass in differing stages of being made into telescope elements to create photograms. In this process, an object is placed on a photosensitive sheet and exposed to sunlight. Glass, a material between visible and invisible, refracts light in curious and complex ways. Understanding refraction underpins the development of vision apparatus such as telescopes, microscopes, binoculars and cameras, devices we use to extend what, where and how we see.

Yvette’s photograms, created with pieces of circular glass abandoned on their way to becoming meticulously specific forms within a cyborg vision apparatus, have a cosmic quality redolent of eclipse images, the disc of the sun or moon skirted by a corona of luminous intensity.

“Ultimately, Photography is subversive, not when it frightens, repels, or even stigmatises, but when it is pensive, when it thinks.”

— Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography 1981

In their various explorations, the artists in AFTERGLOW draw our attention to the deep epistemic, contingent, and irregular potentials of things lost or being lost, events out of sight or obscured, and methods and processes moved on from. They create images to hold us for a while in spaces of reflection, to tickle a neglected sense of fascination obscured in a subconscious pre-modern undertow of magical or numinous irrationality.

© Gary Warner, Gadigal/Sydney 2024